VII

PERSONA NON GRATA

We shall not attempt to deny that Downy has an unprincipled relative. While it is no discredit, it is a great misfortune to Downy, who is often murdered merely because he looks a little, a very little, like this disreputable cousin of his. The real offender is the sapsucker, that musical genius of whom we have already spoken.

The popular belief is that every woodpecker is a sapsucker, and that every hole he digs in a tree is an injury to the tree. We have seen that every hole Downy digs is a benefit, and now we wish to learn why it is that the sapsucker’s work is any more injurious than other woodpeckers’ holes; how we are to recognize the sapsucker’s work; and how much damage he does. We will do what the scientists often do,—examine the bird’s work and make it tell us the story. There is no danger of hurting the sapsucker’s reputation. The farmer could have no worse opinion of him; and, though the case has been appealed to the higher courts of science more than once,[34] where the sapsucker’s cause has been eloquently and ably defended, the verdict has gone against him. Scientists now do not deny that the sapsucker does harm. But his worst injury is less in the damage he does to the trees than in the ill-will and suspicion he creates against woodpeckers which do no harm at all. If you will study the picture and the descriptions in the Key to the Woodpeckers, you will be able to recognize the sapsucker and his nearest relatives, whether in the East or in the West. But all sapsuckers may be known by their pale yellowish under parts, and by the work they leave behind. As the yellow-bellied sapsucker is the only one found east of the Rocky Mountains, we shall speak only of him and his work.

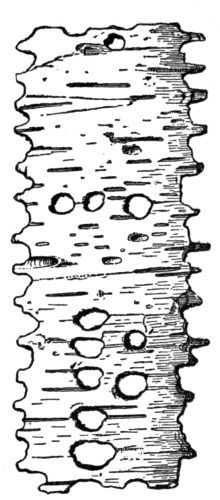

Here is a specimen of the yellow-bellied sapsucker’s work which I picked up under the tree from which it had fallen. We do not need to inquire whether the tree was injured by its falling, for we know that the loss of sound and healthy bark is always a damage. Was this sound bark? Yes, because it is still firm and new. The sap in it dried quickly, showing that neither disease nor worms caused it to fall; it is clean and hard on the back, showing that it came from a live tree, not from a dead, rotting log.

How do I know that a bird caused it to fall? The marks are precisely such as are always left by a woodpecker’s bill. How do I know that it was a sapsucker’s work? Because no other woodpecker has the habit which characterizes the sapsucker, of sinking holes in straight lines. The sapsuckers drill lines of holes sometimes around and sometimes up and down the tree-trunk, but almost always in rings or belts about the trunk or branches. A girdle may be but a single line of holes, or it may consist of four or five, or more, lines. Sometimes a band will be two feet wide; and as many as eight hundred holes have been counted on the trunk of a single tree. Such extensive peckings, however, are to be expected only on large forest trees. Most fruit and ornamental trees are girdled a few times about the trunk, and about the principal branches just below the nodes, or forks.

Why did the bird dig these holes? There are three things that he might have obtained,—sap, the inner bark, and boring larvæ. Some naturalists have suggested a fourth as possible,—the insects that would be attracted by the sap.

We will see what the piece of bark tells us. It is four and a half inches long, by an inch and a half wide, and its area of six and three fourths square inches has forty-four punctures. Does this look as if the bird were digging grubs? Do borers live in such straight little streets? The number and arrangement of the holes show that he was not seeking borers, while the naturalists tell us that he never eats a borer unless by accident. What did he get? Undoubtedly he pecked away some of the inner bark. All these holes are much larger on the back side of the specimen than on the outer surface. While the damp inner bark would shrink a little on exposure to the air, we know that it could not shrink as much as this; and investigation has shown that the sapsucker feeds largely on just such food, for it has been found in his stomach. Two other possible food-substances remain,—sap and insects. We know that the sapsucker eats many insects, but it is impossible to prove that he intended these holes for insect lures. Sap he might have gotten from them, if he wished it. We know that the white birch is full of excellent sap, from which can be made a birch candy, somewhat bitter, but nearly as good as horehound candy. The rock and red maples and the white canoe birch are the only trees in our Northern forests from which we make candy. A strong probability that our bird wanted sap is indicated by the arrangement of the holes. Usually he drills his holes in rings around the tree-trunk, but in this instance his longest lines of holes are vertical. If our sapsucker was drilling for sap, he arranged his holes so that it would almost run into his mouth, lazy bird!

Our piece of bark has taught us:—

- That the sapsucker injured this tree.

- That he was not after grubs.

- That he got, and undoubtedly ate, the soft inner bark of the tree.

- That he got, and may have drunk, the sap.

We could not infer any more from a single instance, but the naturalists assure us that the bird is in the habit of injuring trees, that he never eats grubs intentionally, and that he eats too much bark for it to be regarded as taken accidentally with other food. About the sap they cannot be so sure, as it digests very quickly. There remain two points to prove: whether the sapsucker drills his holes for the sake of the sap, or for insects attracted by the sap, provided that he eats anything but the inner bark.

Our little specimen can tell us no more, but two mountain ash trees which were intimate acquaintances of mine from childhood can go on with the story. Do not be surprised that I speak of them as friends; the naturalist who does not make friends of the creatures and plants about will hear few stories from them. These trees would not tell this tale to any one but an intimate acquaintance. Let us hear what they have to say about the sapsucker.

There are in the garden of my old home two mountain ash trees, thirty-six years of age, each having grown from a sprout that sprang up beside an older tree cut down in 1863. They stand not more than two rods apart; have the same soil, the same amount of sun and rain, the same exposure to wind, and equal care. During all the years of my childhood one was a perfectly healthy tree, full of fruit in its season, while the other bore only scanty crops, and was always troubled with cracked and scaling bark. To-day the unhealthy tree is more vigorous than ever before, while its formerly stalwart brother stands a mere wreck of its former life and beauty. What should be the cause of such a remarkable change when all conditions of growth have remained the same?

I admit that there is some internal difference in the trees, for all the birds tell me of it. One has always borne larger and more abundant fruit than the other, but this is no reason why the birds should strip all the berries from that tree before eating any from the other. When we know that the favorite tree stands directly in front of the windows of a much-used room and overhangs a frequented garden path, the preference becomes more marked. But robins, grosbeaks, purple finches, and the whole berry-eating tribe agree to choose one and neglect the other, and even the spring migrants will leave the gay red tassels of fruit still swinging on one tree, to scratch over the leaves and eat the fallen berries that lie beneath the other. My own taste is not keen in choosing between bitter berries, but the birds all agree that there is a decided difference in these trees,—did agree, I should say, for their favorite is the tree that is dying. Evidently this is a question of taste. It is interesting to observe that the sapsucker, which was never seen to touch the fruit of the trees, agrees with the fruit-eating birds. Nearly all his punctures were in the tree now dying. Is there a difference in the taste of the sap? Does the taste of the sap affect the taste of the fruit? Or is it merely a question of quantity? If he comes for sap, he prefers one tree to the other on the score either of better quality or greater quantity.

We will discuss later whether it is sap that he wishes: all that now concerns us is to note that the internal difference, whatever it is, is in favor of the tree that is dying; while the only external difference appears to be the marks left by the sapsucker. While one tree is sparingly marked by him, the other is tattooed with his punctures, placed in single rings and in belts around trunk and branches beneath every fork. It is a law of reasoning that, when every condition but one is the same and the effects are different, the one exceptional condition is the cause of the difference. If these trees are alike in everything except the work of the sapsucker (the only internal difference apparently offsetting his work in part), what inference do we draw as to the effect of his work?

We presume that he is killing the tree, without as yet knowing how he does it. What is his object? Good observers have stated that he draws a little sap in order to attract flies and wasps; that the sap is not drawn for its own sake, but as a bait for insects. Is this theory true?

The first objection is that it is improbable. The sapsucker is a retiring, woodland bird that would hesitate to come into a town garden a mile away from the nearest woods unless to get something he could not find in the woods. Had he wanted insects, he would have tapped a tree in the woods, or else he would have caught them in his usual flycatching fashion. There must have been something about the mountain ash tree that he craved. As it is a very rare tree in the vicinity of my home, the sapsucker’s only chance to satisfy his longing was by coming to some town garden like our own.

Not only is the theory improbable, but it fails to explain the sapsucker’s actions in this instance. In twenty years he was never seen to catch an insect that was attracted by the sap he drew. This does not deny that he may have caught insects now and then, but it does deny that he set the sap running for a lure. As he was never far away, and was sometimes only four and a half feet by measure from a chamber window, all that he did could be seen. He did not catch insects at his holes. He drank sap and ate bark.

Finally, the theory is not only improbable and inadequate, but in this instance it is impossible. I do not remember seeing a sapsucker in the tree in the spring; if he came in the summer, it must have been at rare intervals; but he was always there in the fall, when the leaves were dropping. At that season the insect hordes had been dispersed by the autumnal frosts, so that we know he did not come for insects.

In the many years during which I watched the sapsuckers—for there were undoubtedly a number of different birds that came, although never more than one at a time—there was such a curious similarity in their actions that it is entirely proper to speak as if the same bird returned year after year. His visits, as I have said, were usually made at the same season. He would come silently and early, with the evident intention of making this an all-day excursion. By eight o’clock he would be seen clinging to a branch and curiously observant of the dining-room window, which at that hour probably excited both his interest and his alarm. Early in the day he showed considerable activity, flitting from limb to limb and sinking a few holes, three or four in a row, usually above the previous upper girdle of the limbs he selected to work upon. After he had tapped several limbs he would sit waiting patiently for the sap to flow, lapping it up quickly when the drop was large enough. At first he would be nervous, taking alarm at noises and wheeling away on his broad wings till his fright was over, when he would steal quietly back to his sap-holes. When not alarmed, his only movement was from one row of holes to another, and he tended them with considerable regularity. As the day wore on he became less excitable, and clung cloddishly to his tree-trunk with ever increasing torpidity, until finally he hung motionless as if intoxicated, tippling in sap, a disheveled, smutty, silent bird, stupefied with drink, with none of that brilliancy of plumage and light-hearted gayety which made him the noisiest and most conspicuous bird of our April woods.

Our mountain ash trees have told us several facts about the sapsucker:—

- That he did not come to eat insects.

- That he did come to drink sap, and that he probably ate the inner bark also.

- That he drank the sap because he liked it, not for some secondary object, as insects.

- That he could detect difference in the quality or quantity of the sap, which caused him to prefer a particular tree.

That this difference apparently was in the taste of the sap, and that the effects of a day’s drinking of mountain ash sap seemed to indicate some intoxicant or narcotic quality in the sap of that particular tree.

That the effect of his work upon the tree was apparently injurious, as it is the only cause assigned of a healthy tree’s dying before a less healthy one of the same age and species, subject all its life to the same conditions.

So much we have learned about this sapsucker’s habits, and now we should like to know why his work is harmful, and why that of the other woodpeckers is not. It is not because he drinks the sap. All the sap he could eat or waste would not harm the tree, if allowed to run out of a few holes. Think how many gallons the sugar-makers drain out of a single tree without killing the tree. But the sugar-maker takes the sap in the spring, when the crude sap is mounting up in the tree, while the sapsucker does not begin his work till midsummer or autumn, when the tree is sending down its elaborated sap to feed the trunk and make it grow. This accounts for the woodpecker’s digging his pits above the lines of the holes already in the tree. The loss of this elaborated sap is a greater injury than the waste of a far larger quantity of crude sap, so that on the season of the year when the sapsucker digs his holes depends in large measure the amount of damage he does. The injury that he does to the wood itself is trivial. He is not a woodpecker except at time of nesting, and most woodpeckers prefer to build in a dead or dying branch, where their work does no hurt. But we know very well that a tree may be a wreck, riven from top to bottom by lightning, split open to the heart by the tempest, entirely hollow the whole length of its trunk, and yet may flourish and bear fruit. The tree lives in its outer layers. It may be crippled in almost any way, if the bark is left uninjured; but if an inch of bark is cut out entirely around the tree, it will die, for the sap can no longer run up and down to nourish it.

This is the sapsucker’s crime: he girdles the tree,—not at his first coming, nor yet at his second, not with one row of holes, nor yet with two; but finally, after years perhaps, when row after row of punctures, each checking a little the flow of sap, have overlapped and offset each other and narrowed the channels through which it could mount and descend, until the flow is stopped. Then the tree dies. It is not the holes he makes, nor the sap he draws, but the way he places his holes that makes the sapsucker an unwelcome visitor. For an unacceptable individual he is to the farmer,—persona non grata, as kings say of ambassadors who do not please their majesties. What shall we do with him, the only black sheep in all the woodpecker flock? Let him alone, unless we are positively sure that we know him from every other kind of woodpecker. The damage he does is trifling compared with what we should do if we made war upon other woodpeckers for some supposed wrong-doing of the sapsucker.

Lee’s Addition:

The trees of the LORD are full of sap, The cedars of Lebanon which He planted, (Psalms 104:16 NKJV)

This is Chapter VII from The Woodpeckers book. Our writer, Fannie Hardy Eckstorm, wrote this in 1901. There are 16 chapters, plus the Forward, which are about the Woodpecker Family here in America. All the chapters can be found on The Woodpeckers page. I added photos to help enhance the article. In 1901, photography was not like today.

Woodpeckers belong to the Picidae – Woodpeckers Family.

It is quite lenghty, but it is also very interesting. I did not know that the Woodpeckers have a “black sheep in the woodpecker flock.”

I am sure the Lord had a reason why He created the Sapsuckers. Why kill all woodpeckers just to get rid on one “bad” one? That sounds like letting the wheat and tares grow together, so that the good wheat isn’t destroyed by picking the tares.

But he said, ‘No, lest while you gather up the tares you also uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest, and at the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, “First gather together the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them, but gather the wheat into my barn.” ‘ ” (Matthew 13:29-30 NKJV)

*

See:

- The Woodpeckers

- Picidae – Woodpeckers Family

- Yellow-bellied Woodpecker – All About Birds

- Yellow-bellied Woodpecker – Wikipedia

- Yellow-bellied Woodpecker – WhatBird

- Yellow-bellied Woodpecker – National Geographic

*

Those very holes were how we determined we had a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker in our yard. The tree is far from our bird viewing windows, so never knew it was here until one of the boys decided to climb that tree this spring. They call it their Monkey Tree. :)

When trying to find out if Sapsuckers can actually harm trees, I found a forum where a man admitted to actually killing them (even though he knew they were protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act). :( It doesn’t bother us if this bird uses our trees, we want our property to be a welcome place for any native species.

I hope you are enjoying your December. We are well blessed here even when life brings unexpected changes. God is so good and faithful.

LikeLike

I agree. The more birds the merrier. You can always figure out somethinginstead of killing the birds.

December has been very busy, but it is every year. Hope to go birding for a day or so next week.

Lord Bless your holiday.

LikeLike

This article is fascinating. I had no idea! I feel sorry for the other woodpeckers who get blamed for his damage, but I also feel sorry for the poor sapsucker. He can’t seem to help being destructive. I have to suppose that the damage he does is the result, somehow, of the fall into sin and the curse in the world. Hopefully, when we are finished with that situation and have a new heaven and a new earth, the little sapsucker will be a bird that does no damage.

When you think in terms of his doing damage being part of the curse resulting from man’s sin, it brings home even more powerfully the words from Romans 8 that say all of creation is groaning as a result of man’s fall and the curse, and that all of creation is eagerly awaiting the total manifestation of redemption. Those little sapsuckers will be very relieved to become birds that do only good, and no harm, to the rest of nature.

Thanks for the article and the education.

LikeLike

Thanks. You always have such a way of saying what I was thinking while writing the article. The curse kept coming to mind. You expressed it much better than I could have.

LikeLike