Yellow-headed Blackbirds: Not Attracted to Life on the Shallow Side

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

Draw nigh to God, and He will draw nigh to you.

(James 4:8a)

(Photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Yellow-headed Blackbirds [Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus] remind me of our need to stay close to God. That takes a bit of explaining, but there is actually a simple connection between staying close to God and the behavior of Yellow-headed Blackbirds (when then gather on the edge of a cattail-encompassed pond).

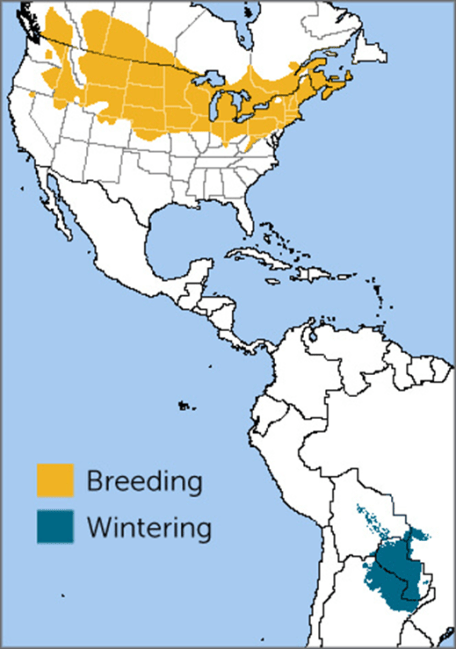

Yellow-headed Blackbirds are found in marshy areas west of the Mississippi River.

(Photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Male much larger than the female; head, neck, and upper breast bright yellow, blackish elsewhere; and conspicuous white markings on the wings. Female duller and lighter, yellow on the chest, throat, and face, no white marks. … Visiting a [yellow-headed blackbird] colony in a marsh or slough in spring is an exciting experience. Some males are always in display flight, with head stooped, feet and tail drooped, wings beating in a slow accentuated way. Some quarrel with neighbors over boundaries while others fly out to feed.

[William A. Niering, WETLANDS (New York, NY: Chanticleer Press / National Audubon Society Nature Guides, 1998), page 600.]

(Photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

The first time, that I saw Yellow-headed Blackbirds, was in Jackson Hole, Wyoming — near the base of the Grand Teton Mountains, not far from the Snake River (and also not far from Yellowstone National Park). It was summer, yet the temperatures were mild — even relatively cool — especially if compared to the scorching hot summers of Texas.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Thus, as part of a working/family vacation — that combined family vacation time (in Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park) with attending a Continuing Legal Education seminar for federal bankruptcy litigators — I was able to enjoy many hours of wildlife viewing (including wonderful birdwatching, plus bull moose — but that’s another story!) in that beautiful part of western Wyoming.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

There was a ponded area near the Jackson Hole visitors’ center, and the ponded area featured flourishing cattails (a wetland plant mentioned in a previous blogpost, “Red-winged Blackbirds: Marsh-loving Icterids”, posted at https://leesbird.com/2023/07/28/red-winged-blackbirds-marsh-loving-icterids/ ). Interestingly the cattail-fringed pond-shore had many perching blackbird “neighbors”; some were red-winged and others were yellow-headed.

(photo credit: Lee & Mary Benfield / Gypsies @ Heart)

Yet there was a noticeable pattern — most of the perching blackbirds, closer into the pond-marsh waters, were yellow-headed, in contrast to the redwings who perched farther away from the wetland pond-shoreline, on the shallower sides of the pond-marsh waters.

This group behavior observation is corroborated by a report posted on the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) website:

The yellow-headed blackbird and red-winged blackbird are often found in the same habitat in the western United States, but yellow-headed blackbirds [being robin-sized] are the larger, more dominant species. They generally nest in deeper water near the center of larger wetlands, while red-winged blackbirds nest along the edges in shallower water.

[ National Wildlife Federation, posted at http://www.nwf.org ]

(Photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

This observation is not a new one — see my earlier blogpost “Yellow-headed and Red-winged Blackbirds: Living on the Inside or the Outside?” (posted at https://leesbird.com/2014/08/04/yellow-headed-and-red-winged-blackbirds-living-on-the-inside-or-the-outside/ ).

So, reconsider the observation made by the NWF author, above: Yellowheads “generally nest in deeper water near the center of larger wetlands”, while redwings “nest along the edges of shallower [i.e., more peripheral] water”. In other words, Yellow-headed Blackbirds congregate closer in, while Red-winged Blackbirds settle farther out.

(photo credit: Roads End Naturalist)

Ornithologist Ellen Horowitz, of the Flathead Audubon Society, gives a more detailed description of this habitat-sharing dynamic, between Yellow-headed blackbirds and their redwing cousins:

Yellow-headed Blackbirds, larger than their red-winged cousins, dominate in areas where both are present. Redwing Blackbirds appear early in spring and exploit all areas of a marsh until the yellow-heads arrive. Territorial interactions between the two are an easily observed bird behavior that is part of the springtime ritual at a marsh. Yellow-headed Blackbirds take over the prime real estate, often located near the center of large wetlands, and oust the redwings to shallower water near the edges.

Nesting colonies of Yellow-headed Blackbirds are found where dense cattails and bulrushes grow in two to four feet of water and where insect life is rich. Some colonies contain as many as 25 to 30 nests within a 15 square foot area. Each adult male stakes his claim within the larger framework of the colony. A polygynous breeder, he mates with several females who nest within his defended territory. The female weaves long strands of wet vegetation around cattails or other tall aquatic plants to form her nest. As the basket-like structure dries, it pulls the supports taught. The location of a nest ranges from 10 to 30 inches above the water. Deep water protects the nest and its occupants from prowling predators — skunks, raccoons and foxes. Tall, thick vegetation hides them from northern harriers and other birds of prey.

During the breeding season, the diet of yellow-headed blackbirds consists primarily of insects and spiders. The birds glean them from the ground, plants, or hawk them from the air. Seeds, including grain, form a major portion of their diet during the rest of the year. Like all Icterids, the yellow-head has a strong, straight, pointed bill and powerful muscles that control its opening and closing. After inserting its bill into the ground or matted vegetation, the yellow-head spreads its bill, which presses against the surrounding substrate to form a cavity. The behavior, known as “gaping,” allows access to hidden food sources.

Yellow-headed blackbirds feed in freshly plowed lands, cultivated fields and pastures during migration. Although they cause some damage to agricultural crops by pulling up seedlings and eating grain, the insects and weed seeds they consume prove more beneficial than harmful.

[ Ellen Horowitz, “Yellow-headed Blackbird”, Flathead Audubon Society, posted at https://flatheadaudubon.org/bird-of-the-month/yellow-headed-blackbird/ ]

[ Quoting Ellen Horowitz, “Yellow-headed Blackkbird”, Flathead Audubon Society, posted at https://flatheadaudubon.org/bird-of-the-month/yellow-headed-blackbird/ ]

Now, with those background facts in mind, consider who some Christians try—in their daily walking through this earthly life—to stay close to God. Think of how the Lord Jesus Christ spoke to multitudes, yet He had only a dozen close disciples (Matthew 10:1-4; Mark 3:13-19; Luke 6:12-16), and even one of those was a money-embezzling fake! (John 6:70), — and, from among those 12 disciples, Christ had 3 who were closest to Him: Peter and 2 sons of Zebedee, James and John (Matthew 17:1).

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Yet many Christians are satisfied with rather worldly lives, not trying very seriously to walk through life close to God. That’s like living at a distance, spiritually speaking, on the “shallow” side, so to speak — like Red-winged Blackbirds who settle for settling in cattails of the shallower pond-marsh waters.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Just as Yellow-headed Blackbirds prefer to be closer to the center of a Jackson Hole pond-marsh, I prefer to live closer to the Lord Jesus Christ–Who is my revered and appreciated Creator, Redeemer, and Shepherd. Reminds me of an old Fanny Crosby hymn:

Draw nigh to God, and He will draw nigh to you.

(James 4:8a)

How about you?

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)