Bird Nests, illustrating God’s Providence

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

There shall the great owl make her nest, and lay, and hatch, and gather under her shadow.

(Isaiah 34:15a)

Sharon Friends of Conservation photo credit

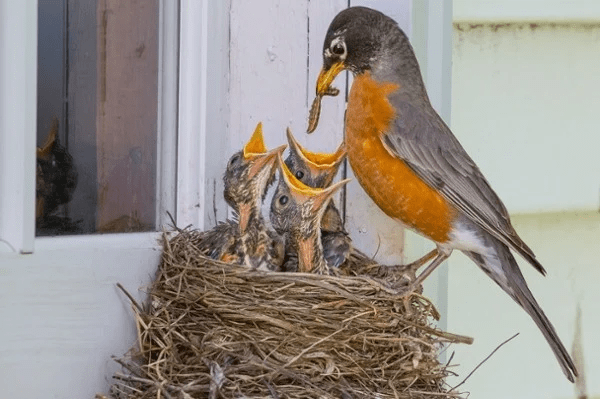

NEST — this simple word “nest” represents an enormously important context for a bird’s early life, and for bird parents, so bird nests are critically important for the life of entire bird families. A baby bird’s beginning is experienced inside a nest. From embryonic egg to hatchling, from hatchling to fledgling, a baby bird’s life adventures are “hatched” inside a nest of some kind. Consequently, nests are the childhood homes to young nestling birds, plus parent birds repeat their multi-generational nest life as they reproduce and nurture the next generation of their own kind.

For most birds, springtime means mating, and mating time means nesting. As soon as nesting begins in earnest, everything changes. The earth becomes quieter, the sight of a bird [displaying to attract a prospective mate] rarer. Despite the seeming tranquility, there’s much ado and excitement among the birds. The joy of expressing the springtime, of finding or reclaiming a mate, has been exchanged for the silence and secrecy of very private moments as birds begin the work of creating their homes.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 7.]

Do you recall the first times you ever saw a bird nest, close up? Did you realize, then, that the nest was “home” to the birds who resided therein?

pixy.org photo credit

And what a variety of nests there are, because God has programmed different birds to build and indwell different types of nests!

The variety of nests in the world of birds is fascinating. Numerous species build elaborate structures. The Dark-necked Tailorbird (Orthotomus atrogularis) builds its nest out of vegetable matter inside two leaves sewn together or in a single large leaf that is also sewn up with a thin length of thread; weaverbirds, and in particular the Sociable Weaverbirds (Philetarius socius), build large collective nests … certain Australian moundbirds (Megapodidae) build huge nests of earth and vegetable matter, using the heat produced as it decomposes to incubate the [compost-buried] eggs. Many species build rudimentary nests, others lay their eggs on the ground, in sand and among pebbles. … The nest is a structure used almost exclusively for reproductive purposes [or as a resting-place] …. The influences of the hormonal system combined with the physiological changes that take place in the bird’s body in the reproductive period determine the construction of the nest. The choice of the site, the materials used and the time taken to build it, and the activity of the male or female in the construction, all vary from species to species.

[Quoting Bologna, 1981, pages 39-42]

By the way, for a sampling of the diverse bird nests of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, see Kathy Reshetiloff’s “Cups, Cavities, Scrapes or Spheres–to Each Bird its own Nest”, CHESAPEAKE BAY JOURNAL, 34(2):40 (April 2024), posted at http://www.bayjournal.com/columns/bay_naturalist/cups-cavities-scrapes-or-spheres-to-each-bird-its-own-nest/article_cbbad062-f0ec-11ee-8cc0-dbe15dde1460.html .

These nests must accommodate the bird family’s collective weight and activities, as well as tolerate foul weather, such as winds and precipitation. Of course, nests constructed upon or inside the ground, such as the mound-nests of the Megapode “incubator bird” (Martin, 1994, pages 43-46), need not be concerned with the weight of the nest.

Some nests are mere scrapes upon a strategic patch of ground. The Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea) is famous for its record-breaking migration treks, from the Arctic regions to the Antarctic regions, and vice versa (Egevang et al., 2010, page 2078), so the Artic Tern cannot afford a nest-building habit, during its breeding season (in the Arctic), that would invest too much time or material in nest-building.

WeForAnimals.com photo credit

Since the Arctic summer is so brief, a simple scrape that does not shorten brooding time is the best solution.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 46].

Other bird nests are burrowed underground or into the side of a muddy riverbank [Peterson & Chalif, 1973, page 112; Cohen, 1993, 50-53]. In Texas prairies, for example, one such underground-dwelling bird is the Burrowing Owl (Speotyto cunicularia).

One of the strangest and most beguiling members of the owl family is the burrowing owl. It lives in a hole in the ground, often on a treeless prairie or desert, and is most frequently seen standing beside its burrow or perched on a nearby fence post. … These charming little owls breed locally in the [Texas] Panhandle and West Texas, frequently associated with prairie dog villages, where they [i.e., the burrowing owls] utilize the ready-made burrows and tunnel systems. Other adapt abandoned homes of ground squirrels and pocket gophers, enlarging them by kicking dirt backwards with their feet.

[Quoting Tveten, 1993, page 173]

Many are designed to be camouflaged or otherwise hidden. Some such tree cavities are claimed by house wrens or certain types of owls, after they are abandoned by the original tree-hole excavators (Cohen, 1993, page 58; Bologna, 1981, pages 52 & 418). However, other tree cavity nests are the products of the birds who inhabit them after they peck them into existence, in the sides of trees or cacti (Shunk, 2016, page 15), such as tree cavity nests of the Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus).

Steve large’s Wildlife Blog photo credit

For secrecy, few hiding places can compare to a tree cavity. … Usually, the foliage of surrounding trees provides ample camouflage; sometimes height is the great advantage. No matter the case, birds nesting in tree cavities are safe from most predators—except tree-climbing snakes and an occasional agile mammal. A tree must be large and structurally sound enough to support a cavity, especially when carved by the Pileated Woodpecker [Dryocopus pileatus]. The Pileated digs a hollow up to two feet into the tree, although the 3½-inch entranceway is only a fraction [of] that size. The Pileated Woodpecker is [providentially] equipped with one of the strongest beaks of all birds, yet excavating comes as no easy chore. The process takes days, and is completed mostly by the male with some assistance from his mate. Many choose dead trees, but even so their efforts may be frustrated by a particularly recalcitrant tree.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 54]

Some bird nests are tree-nestled demitasses, such as large cup-shaped nests of the American Crow (Corvus brachyrynchos), the medium-sized cup-nests of the Magnolia Warbler (Dendroica magnolia), and the fragile mini-nests of most hummingbirds, including the Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus).

AnimalSpot.net photo credit

RUFOUS HUMMINGBIRD: Nest of downy plant fibers and moss, covered with lichens, held together with spider’s silk; placed on downward-sloping limb of tree or shrub.

[Quoting Stokes & Stokes, 1996, page 263]

Even the most careful observer would be challenged to locate a hummingbird’s nest. This smallest of [bird] nests is nearly impossible to find, not only because of its size [~2 inches diameter/width of nest exterior, with ~1 inch diameter/width of nest’s inner cup], but as a result of the plant camouflage the female incorporates into the structure. Because of the importance of camouflage, males are not welcome visitors to the hummingbird nest. Their bright colors draw too much attention and might endanger the offspring, so they take no part in nest-building, incubation, or chick-rearing. Often they return after the chicks are fledged and help produce a second brood in the same season. … Not every bird could manage a cup nest. Because of the high walls [which prevent the nestling young from tumbling out by accident], a cup must be entered from above, a feat best accomplished by skilled aviators such as songbirds. Master of wing control [as demonstrated by multi-directional flight and hovering], the hummingbird is a natural cup nester.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 64]

Since hummingbirds are tiny birds, it is unsurprising that their nests are likewise (realtively) tiny. However, hatchling hummingbird young do more than eat in those tiny nests—they also learn about life, especially from parental teaching:

The staff at ICR [i.e., the Institute for Creation Research] … noticed months ago that an adult bird was weaving a nest on a palm frond. Being a science organization and lovers of God’s living creation, we closely followed the maternal events as they unfolded. The tiny eggs hatched and in due time, the two rapidly-growing hatchlings were literally bursting from the confines of their nest. It was interesting that the mother, perched on a nearby branch (always the same one), would intently watch her little ones in the nest. She would occasionally zoom around the nest, showing her crouching, bewildered offspring that “this is how you do it!”

[Sherwin, 2006]

Other bird nests are quite roomy, resembling hanging sacks or book-bags, such as the pocket-like sack-nest of the Baltimore Oriole (Icterus galbula).

Carol Smith / Carol’s View of New England photo credit

Orioles are as well known for their nests as they are for any other aspect of their behavior. The nest is a long woven sack, suspended from the tip of a drooping branch. These nests are obvious in winter, especially hanging over roads, and it’s always interesting to see how many Orioles actually nested in your area, even though you were unaware of them during the breeding season [which is when the orioles’ family privacy is most important!]. Usually the female builds the nest. First a few long fibers are attached to the branch and looped underneath. After that, she brings other fibers one at a time and pushes them through one side, and then arbitrarily pulls fibers in from the other side. The actions [appear] random … [yet] she gradually creates a suspended mass of material. Then, entering from near the top, she lines it with soft material such as feathers, grasses, wool, and dandelion or willow fuzz. The nest can take from five to eight or more days to complete. Orioles usually build a new nest each year, but in some instances they have been known to repair old nests. When building a new nest, they frequently take [and recycle] material from one of their old nests or some other bird’s nest.

[Quoting Stokes & Stokes, 1983, page 231]

Some bird nests are mostly reshaped mud, such as the pottery-like mud-ness of the Rufous Ovenbird (Firnarius rufus), the Cliff Swallow (Hirundo pyrrhonota), the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), and the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber).

Annandale Advocate photo credit

BANK SWALLOW (a/k/a SAND MARTIN): It usually nests near water in holes in steep banks [e.g., inside a nesting hole within a muddy riverbank], either natural or artificial, of earth or sand. The hole is made by both adults and ends in a wider space [e.g., a pocketed riparian mudbank cavity], where the female lays clutches of 3-7 eggs (most often 4 or 5). Both sexes incubate the eggs for 12-16 days. The nidicolous [i.e., nesting for a long time before fledging] nestlings are reared by both parents and stay in the nest for about 19 days [which is a relatively long time before fledging]. They feed on flying insects.

[Quoting Bologna, 1981, page 353]

Mud is an excellent choice of nesting material. When it is cemented into place, mud creates a sturdy nest that is nearly impermeable to any threat but rain, at least for the time needed to raise a family of chicks. Cliff Swallows Hirundo pyrrhonota) build their nests as do most other mud-nesters, in stages. As many as one thousand [1,000!] mud pellets, each carried separately to the site and placed in layers, are needed to complete the task. Before each succeeding [mud-nest] layer can be added, the previous one must dry completely [unlike brick masonry courses constructed by human bricklayers!]. Too much weight, and the nest could topple over. The whole tasks needs about two weeks to complete and may take even longer during periods of drought or too much rain. A mud hole seems almost alive when dozens of Cliff Swallows are jockeying for the choicest mud they can find.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 74]

Some bird nests are located on shorelines of freshwater or brackish water, such as nests of Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) and nests of Common Loon (Gavia immer). Likewise, some birds nests are located on oceanic beaches and rocky seashore cliffsides, such as nests of Red-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa brevirostris) and nests of Thick-billed Murres (Uria lomvia).

Many aquatic birds build their nests very close to or just on top of the water. Some birds, such as coots, build their own private nest islands on the water, while grebes anchor floating platforms to a nearby water plant. As long as the eggs stay dry (and out of the jaws of a predator), the unhatched chicks remain safe. … Though loons fish in both fresh and salt water, they nest near fresh water [usually lentic freshwater, such as ponds and lakes] only. Free of the currents and tidal motion of seawater, the calmer waters of inland lakes are easier for neonates to negotiate while learning the diving techniques crucial for their adult survival.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 78]

The [Common Loon] nests are usually sheltered by surrounding vegetation and upon first being built are right at the water’s edge. …. Nests are built of earth, grasses, moss, [and/or] dense floating vegetation. Little in the way of a nest is built before the eggs are laid. The nest at this time is usually only a little depression in the substrate with a small amount of [added] material collected around it.

[Quoting Stokes & Stokes, 1989, page 18]

They [i.e., Double-crested Cormorants] nest in colonies, their stick nests usually in cottonwoods near or over water. Cormorants are abundant on the lakes and reservoirs of eastern Colorado in summer; a few remain in winter.

[Quoting Gray, 1998, page 27]

Some bird nests are in rocks, often at high altitudes.

The vivid description in [verses 27-28] Job 39 must surely refer to the griffon-vulture [Gyps fulvus]: ‘Doth the eagle mount up at thy command, and make her nest on high? She dwelleth and abideth on the rock, upon the crag of the rock, and the strong place.’ This passage well describes a typical nesting-site.

[Quoting Cansdale, 1976, page 144].

The size of Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) nests is impressive—some eagle nests are built to colossal sizes, more than 12 feet deep, 8 feet wide, and weighing up to a ton!

[Cohen, 1993, pages 62-63].

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) uses a platform nest as its base and then builds a more complicated cup nest into the surface. If disturbed during egg-laying or early chick-rearing, a Bald Eagle pair may abandon tis nest. [Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 62]

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 62]

Eagles—like many other territorial birds of prey—often nest far from other eagles, yet this is obviously not characteristic of Bald Eagle populations along the coasts of Southeastern Alaska (Kavanaugh, 1997, page 59; personal observations during summer itineraries aboard cruise ships, serving a historian/naturalist, during AD2000, AD2001, and after).

Thousands [of Bald Eagles, migrating seasonally to the Alaska Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve] congregate to feed on spawning salmon in the Chilkat [River] Valley in autumn and early winter.

[Quoting Kavanaugh, 1997, page 59]

Many bird populations nest in colonies, with some wading bird colonies called “rookeries” (Griggs, 1997, page 41), in keeping with other gregarious habits that justify the old saying: “birds of a feather flock together”. Such gregarious behavior certainly includes the wonderful icterids we call grackles, often seen congregating in or above parking lots, such as the Common Grackle (Quiscalus quiscula) and the Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus).

Grackle nest-building may occur over a period of up to six weeks or even more, and in these extended cases seems to be closely tied with pair formation. Grackles are somewhat colonial in their nesting habits, many pairs often nesting in the same area. After a pair have become established they spend most of their time at a breeding site, first just exploring: visiting old nests and hopping about prospective nest sites. During these activities [as with similar activities by human pairs] the female is always in the lead.

[Quoting Stokes,1979, page 296]

Thus, for God’s multitude of bird varieties God programmed those birds to make and to use a prodigious variety of bird nests. This fits God’s Genesis Mandate, for birds to be fruitful, multiply, and fill the earth — because biodiversity is enhanced by a variety of habitats to house that biodiversity (Johnson, 2012a, pages 10-12).

Many bird nests (such as hummingbird nests) go unnoticed by human eyes, yet our Heavenly Father always notices and cares about bird nests, everywhere and at all times, because He cares about the birds whose needs are met by those nests.

Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? And one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father.

(Matthew 10:29)

The diversity of avian nesting habits displays God’s love for variety (Johnson, 2012b, pages 8-9), as one would expect, since we see countless proofs of God’s love of variety in how animals (including birds of all kinds) are fruitful, multiply, and fill niches all over the earth (Johnson, 2012a, pages 10-12).

Accordingly, expect to find variety in bird nests.

A hummingbird hovers over a spider’s web, spending several seconds latching onto a thread of silk [to be incorporated as stabilizing material for the hummer’s coin-sized nest]. A woodpecker suspends his tree-drumming and instead works on excavating a nest hole with his mate. A shorebird slinks into a quiet area unnoticed and lays her single egg on [a strategically selected patch of] bare sand. In the privacy of their own world[s], often far beyond human ken, birds settle down to build their nests and breed young.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 7.]

The importance of bird nests is no surprise, because nest life is at the heart of a bird population’s critical habitat. Nest life is where a parental generation of birds facilitate the launching of the next (i.e., filial) generation of those birds [Bologna, 1981, pages 37-45; Cohen, 1993, pages 7-8.]

But, the physiology of birds requires a nest life that differs from many non-birds, because birds (including pre-hatched birds) are warm-blooded animals.

What makes birds different from other egg-laying creatures is that the embryo inside each egg is as warm-blooded as a human, and like a human, requires the warmth provided by its parent, or by an adequate substitute, to develop and to thrive. Because it is so fragile, the egg must be coddled in a secure place until its occupant is ready to leave and face the rigors of the outside world. Encased in its [calcium carbonate-structured] shell, the tiny chick’s only hope is that its parents [or foster-parents] do know what is best. The nest the adult birds provide furnishes the warmth and protection necessary for the chicks’ survival.

[Quoting Cohen, 1993, page 8.]

Nests are so important, because God made them to have useful value, so we should expect them to be mentioned within the HOLY BIBLE’s pages. And, sure enough, the holy Scriptures refer to bird nests, repeatedly. A few such examples follow.

Before reviewing those examples, however, it is worth noticing that the usual Hebrew noun translated “nest” is qên (Wigram, 20123, page 1111), which first appears in Genesis 6:14 (referring to “homes” aboard Noah’s Ark), where the King James Version of the English Bible translates it as “rooms”. Yet, even in that Ark housing context, a qên was one of many temporal “homes” (i.e., onboard chambers, like “cabins” or “staterooms” within an ocean-faring cruise ship), used for security and protection from hostile external conditions.

Based upon etymologically related Hebrew words (Wigram, 20123, pages 1111-1112), it appears that the underlying connotation is the idea of specifically claimed property (i.e., acquired and possessed as “private” property) that belongs to a specific individual, or to a specific group (such as a specific family).

Accordingly, the Hebrew words for “nest” (both as a noun and as a verb) denote the structural home of a bird family, that belongs to that bird family—the family nest is specifically claimed property (i.e., acquired and possessed as “private” property), situated within the bird family’s ecological neighborhood.

- Location, location, location: where you nest matters!

Where a bird nest is positioned is important. Maybe the best place for a nest—such as an Osprey nest—is high upon a relatively inaccessible rocky clifftop, or within the higher branches of a tall tree (Stokes & Stokes, 1989, page 163).

And he looked on the Kenites, and took up his parable, and said, ‘Strong is thy dwelling-place, and thou puttest [i.e., you position] thy nest in a rock.’

(Numbers 24:21, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

And for many large birds of prey, such as eagles, nesting in high places is the way to go. (Perhaps such birds feel “high and mighty”!)

Thy terribleness hath deceived thee, and the pride of thine heart, O thou that dwellest in the clefts of the rock, who holds the height of the hill; though thou shouldest make thy nest as high as the eagle, I will bring thee down from thence, saith the Lord.

(Jeremiah 49:16, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

Though thou exalt thyself as the eagle, and though thou set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring thee down, saith the Lord.

(Obadiah 1:4, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

Woe to him that covets an evil covetousness to his house, that he may set his nest on high, that he may be delivered from the power of evil! )

(Habakkuk 2:9, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

No need for humans to feel “high and mighty” – God resists the proud but he upholds the humble-hearted. (And pride routinely “goeth” before a fall.)

2. Multi-generational reproductive success is priority!

Birds of prey include hawks, eagles, owls, and more.

Yet birds themselves are often prey to predators of many kinds, including humans who eat birds, both domesticated and wild—such as chicken, turkey, goose, and the eggs fo many kinds of birds. But if one generation of predators greedily consumes all of a prey population, the next generation of those predators would be deprived of a food source, which would be harmful to both the predator population and the prey population.

Accordingly, it is good for a generation of predators to only eat a limited amount of a prey population, so that future generations of both predators and prey can benefit (from continued reproductive success of the prey population. That stewardship principle—applying restraint in lieu of greedy wastefulness—is what Moses commanded the Israelites as a conservation law for their future entry into and settlement in the Promised Land of Canaan.

If a bird’s nest chance to be before thee in the way in any tree, or on the ground, whether they be young ones, or eggs, and the mother sitting upon the young, or upon the eggs, thou shalt not take the mother with the young; but thou shalt in any wise let the mother go, and take the young to thee; that it may be well with thee, and that thou mayest prolong days. (Deuteronomy 22:6-7, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

(Deuteronomy 22:6-7, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

3. Nests are where good parenting is needed!

How eagle parents treat their young has been a subject of some confusion over the years, due to a less-than-clear-and-accurate translation of Deuteronomy 32:11. That confusion has already been addressed in an earlier article (Johnson, 2020, pages 57-59) examining that all-too-often misinterpreted passage, so that discussion will not be repeated here.

Suffice it to say, here, that eagle parents care for their young! Like many (but not all) animal parents, eagle parents go to great efforts to raise their nestling children, training them, from hatchlings unto fledglings, for their future lives.

As an eagle, he [i.e., God, in relation to His people Israel] stirs up his [i.e., God’s] nest, he {i.e., God] flutters over his [i.e., God’s] young, he [I.e., God] spreads abroad his [i.e., God’s] wings, he [i.e., God] taketh them, he [i.e., God] bears them [i.e., the Israelites as God’s people] on his [i.e., God’s] wings….

(Deuteronomy 32:11, literal translation, with editorial clarifications: “nest” [qên] as metaphoric noun)

This is comparable to how the Lord Jesus Christ compared His willingness to protect Jews to a mother hen’s protectiveness, as demonstrated in her welcoming and refuge-providing wingspread, noted in Matthew 23:37 and also in Luke 13:34.

4. Nests should be places of domestic security: “home sweet home”.

Then I said, I shall die in my nest, and I shall multiply my days as the sand.

(Job 29:18, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

The patriarch Job, unto his “friendly” counsellors, once lamented his former life of blessing, before his torturous trials were suddenly dumped upon his head. Job related how he expected to live a long life of uninterrupted blessing, ultimately dying at peace in his own “nest” (i.e., “home sweet home”). But, God had other plans—ultimately better (albeit bumpier) plans for Job’s earthly pilgrimage.

5. The ability, of birds to make nests, is God-given, i.e., God-programmed.

Doth the eagle mount up at thy command, and make her nest on high?

(Job 39:27, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

The eagle was designed (i.e., pre-programmed) with built-in abilities and inclinations, endowed at creation by the Lord Jesus Christ, to make its nest in high places (Obadiah 1:4), and to mount up into the air suing thermal air currents.

The eagle did not invent these purposeful traits; God designed the eagle’s physical traits and its pre-programmed abilities, including the know-how (and the how-to) needed for successfully building eyries atop high montane places or in tall trees. For more on this Scripture about eagle behavior, see an earlier CRSQ article (Johnson, 2021, page 290).

6. Nests are for raising children, i.e., the next generation.

Yea, the sparrow hath found a house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, even thine altars, O Lord of hosts, my King, and my God.

(Psalm 84:3, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

Notice that the sparrow’s “house” is parallel in meaning to the “nest’ of the swallow. In other words, a “nest” is a “house” for dwelling in, and especially for raising young in.

7. Particular types of nests are selected according who will be living therein.

Where the birds make their nests: as for the stork, the fir trees are her house.

(Psalm 104:17, with “nest” [qânan] as verb)

In the above-quoted psalm we are reminded that storks are known to make their homes within the branches of fir trees. Storks are also known as predictable migrants—see Jeremiah 8:7 (Johnson, 2013).

8. Wandering from the security of the nest can lead to many dangers.

As a bird that wanders from her nest, so is a man that wanders from his place.

(Proverbs 27:8, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

For it shall be, that, as a wandering bird cast out of the nest, so the daughters of Moab shall be at the fords of Arnon. (Isaiah 16:2, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

One of the advantages of many bird nests is camouflage—being hidden from the sight of hungry predators. There is a security that comes with staying inside one’s proper home. Not that any home (or nest) is “bulletproof” from danger, but there are often many more dangers lurking about, the farther that one wanders away from home. (The same is true for young who are expelled from home.)

Consequently, the high mortality rate is why birds routinely try to raise more hatchlings than themselves. In other words, two parent birds need to strive for replacing themselves with more than just two children, in order to mitigate the risks that their progeny will become prey (literally “dead meat”) before they progeny can successfully reproduce the next generation.

[NOTE: the overall concept of multi-generational replacement, as a matter of population biology, is discussed in my population biology article “Post-Flood Repopulation: From 8 to 8,000,000,000!” posted at www.icr.org/article/post-flood-repopulation-from-8-8000000000 .]

9. Bird eggs are a valuable source of good (i.e., nutritionally rich) food.

And my hand hath found as a nest the riches of the people: and as one gathers eggs that are left, have I gathered all the earth; and there was none that moved the wing, or opened the mouth, or peeped.

(Isaiah 10:14, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

Isaiah stated the obvious—eggs are valuable; in fact, they are like a store of “riches”, nutritionally speaking. This nutrition fact concurs with the mention of eggs as a “good” food, in contrast to bad food. See Luke 11:11-13, where giving eggs to eat is recognized (by the Lord Jesus Christ Himself, the Creator of all food) as “good gifts to your children”.

10. Places are recognized as “wild places”, if dominated by many predators.

There shall the great owl make her nest, and lay, and hatch, and gather under her shadow; there shall the vultures also be gathered, everyone with her mate.

(Isaiah 34:15, with “nest” [qânan] as verb)

Isaiah’s somber prophecy warns that God will be judging (i.e., punishing) the Edomites, because of the Edomites’ wicked mistreatment of Israelites (see Isaiah 34:6-8); the resultant judgment includes severe desolation of the Edomites’ land—which desolation shall include Edomite lands becoming overtaken by birds of prey (see Isaiah 34:10-16). Because Edomite lands, in the prophesied future, will be dominated by nests of predatory animals—including predatory birds—such lands will become “wild places” (i.e., wildernesses), not fit for human habitation.

11. Flexibility increases opportunities to “fit” and “fill” different situations.

O ye that dwell in Moab, leave the cities, and dwell in the rock, and be like the dove that makes her nest in the sides of the hole’s mouth.

(Jeremiah 48:28, with “nest” [qânan] as verb)

For example, doves (which include pigeons), are famous for resiliently adjusting themselves to the most diverse of habitats–this is a behavioral trait that this writer has observed frequently, over the years–even in the most unlikely of habitats. Decades ago, this writer (with family members) was exploring an underground “lava tube” cave at Craters of the Moon–a park (designated as a “national monument”), in Idaho. Inside this most ecologically inhospitable venue, perched within a crack in the cavernous ceiling, there was a nest with two pigeons therein! Doves can live successfully almost anywhere – they are peaceful, yet flexible and opportunistic “generalists”.

12. Tree branches are often a hospitable home for nesting birds.

All the fowls of heaven made their nests in his boughs, and under his branches did all the beasts of the field bring forth their young, and under his shadow dwelt all great nations.

(Ezekiel 31:6, with “nest” [qânan] as verb)

The tree that thou sawest, which grew, and was strong, whose height reached unto the heaven, and the sight thereof to all the earth, whose leaves were fair, and the fruit thereof much, and in it was meat for all; under which the beasts of the field dwelt, and upon whose branches the fowls of the heaven had their habitation.

(Daniel 4:20-21)

Even in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream he recognized that tree branches (a/k/a boughs) are good sites for bird nests!

13. Nests, although sturdy and secure, are only temporal.

Though thou exalt thyself as the eagle, and though thou set thy nest among the stars, thence will I bring thee down, saith the Lord.

(Obadiah 1:4, with “nest” [qên] as noun)

Eagle nests are sturdy and secure – setting records for their size and weight (as noted above) – yet they too are, after all, only temporal. This provides a good reminder about this passing world. This world will “groan” till the Lord Jesus cancels the curse of sin and death (Romans 8:22-23; 1st Corinthians 15). Till then, we too “groan” (2nd Corinthians 5:2-4).

14. Christ prepared for bird homes via nesting habitats and nesting skills.

And Jesus saith unto him, The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head.

(Matthew 8:20, with “nests” [κατασκηνωσεις] as noun)

And Jesus said unto him, Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head.

(Luke 9:58, with “nest” [κατασκηνωσεις] as noun)

Behold the kindness of our Lord Jesus Christ: He did not insist on having a “home” when He came to Earth to be our Savior. Christ was goal-oriented, undistracted, and not fixated on the things of this passing world.

However, as our kind Creator, He even prepared fitting homes for His multifarious animal creatures, such as foxes and “birds of the air”. Speaking of “home”, it is the very Creator-Redeemer, our Lord Jesus Christ, Who is our true home.

Accordingly, settling (domesticating) specific niches in the earth—even migratory stopover homes—and utilizing home bases for family life activities is needful to fill the multitude of Earth’s multifarious habitats. To achieve this goal, God has providentially equipped creatures with physical bodies (with helpful anatomies and physiologies) and programmed bio-informational instructions (coding and equipping for habitat-interactive behaviors) that are fitted to the dynamic challenges of physical environments (and biotic communities) all over the globe. As earthbound pilgrims, we pass through this mortal life (Hebrews 11:13; 1 Peter 2:11), interfacing with an all-too-often hostile culture (Hebrews 11:36-38). We long for a truly secure home—where we really belong. But, as Christians, what is our true home? It is not residential real estate housing (Philippians 3:20; Hebrews 11:8-14). Our true homes are not even the earthly bodies that we temporally inhabit, although they are the “tents” we know best (2 Corinthians 5:1-4; 2 Peter 1:13). For Christians, ultimately, our real eternal home is God Himself (Psalm 90:1; 2 Corinthians 5:6; John 14:2-6). As our Creator, He started us. As our Redeemer, we finish with Him. What a homecoming we wait for!

{Quoting Johnson, 2015, page 20)

Maybe there are more examples, of bird nests being mentioned in Scripture. But, at least, the examples listed above show that bird nests are important, so important (to God) that they merit repeated mention, in the only book that God Himself wrote.

REFERENCES

Bologna, Gianfranco. 1981. A Guide to Birds of the World. English translation by Arnoldo Mondadori. Fireside Books / Simon & Schuster, New York, NY.

Cansdale, George S. 1976. All the Animals of the Bible Lands. Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI.

Cohen, Sharon A. 1993. Bird Nests. Harper Collins, San Francisco, CA.

Egevang, Carsten, Iain J. Stenhouse, Richard A. Phillips, & Janet R. D. Silk. 2010. Tracking of Arctic terns (Sterna paradisaea) reveals longest animal migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107(5):2078-2081.

Gray, Mary Taylor. 1998. The Guide to Colorado Birds. Westcliffe Press, Englewood, CO.

Griggs, Jack. 1997. All the Birds of North America. Harper Collins, New York, NY.

Johnson, James J. S. 2012a. God Fitted Habitats for Biodiversity. Acts & Facts. 41(3):10-12 (March 2012), posted at www.icr.org/article/god-fitted-habitats-for-biodiversity .

Johnson, James J. S. 2012b. Valuing God’s Variety. Acts & Facts. 41(9):8-9 (September 2012), posted at www.icr.org/article/valuing-gods-variety .

Johnson, James J. S. 2013. A Lesson from the Stork. Days of Praise (December 22, 2013), posted at www.icr.org/article/lesson-from-stork .

Johnson, James J. S. 2015. Why We Want to Go Home. Acts & Facts. 44(4):20 (April 2015), posted at www.icr.org/article/why-we-want-go-home .

Johnson, James J. S. 2020. Clarifying Confusion about Eagles’ Wings. CRSQ. 57(1):57-59 (summer 2020).

Johnson, James J. S. 2021. Doxological Biodiversity in Job Chapter 39: God’s Wisdom and Providence as the Caring Creator, Exhibited in the Creation Ecology of Wildlife. CRSQ. 57(4):286-291 (spring 2021).

Kavanaugh, James. 1997. The Nature of Alaska: An Introduction to Familiar Plants and Animals and Natural Attractions. Waterford Press, Blaine, WA.

Martin, Jobe. 1994. The Evolution of a Creationist. Biblicla Discipleship Ministries, Rockwall, TX.

Peterson, Roger Tory, & Edward L. Chalif. 1973. A Field Guide to Mexican Birds Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

Sherwin, Frank. 2006. Hummingbirds at ICR. Acts & Facts. 35(9):unpaginated.

Shunk, Stephen A. 2016. Peterson Reference Guide to Woodpeckers of North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, MA.

Stokes, Donald. 1979. Stokes Guide to Bird Behavior, Volume I. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, MA.

Stokes, Donald, & Lillian Stokes. 1983. Stokes Guide to Bird Behavior, Volume II. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, MA.

Stokes, Donald, & Lillian Stokes. 1989. Stokes Guide to Bird Behavior, Volume III. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, MA.

Stokes, Donald, & Lillian Stokes. 1996. Stokes Field Guide to Birds: Western Region. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, MA.

Tveten, John L. 1993. The Birds of Texas. Shearer Publishing, Fredericksburg, TX.

Wigram, George V. 2013. The Englishman’s Hebrew Concordance of the Old Testament, 3rd edition. Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody, MA (originally published in 1874, by Samuel Bagster & Sons, London, UK).

(BirdNote.org photo credit)