Dr. James J. S. Johnson

For the invisible things of Him [i.e., the God of the Bible] from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and deity; so that they are without excuse [αναπολογητους]; because that, when they knew God, they glorified Him not as God, neither were thankful; but they became vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkened. (Romans 1:20-21)

Wikipedia / Charles J. Sharp photo credit

The two inexcusable sins, routinely committed by evolutionist fools [and notice that the term “fools” is factually appropriate, because Romans 1:21 says that “their foolish heart was darkened”], are the inexcusable failure to glorify God as the Creator He ubiquitously proves Himself to be — plus the inexcusable failure to give thanks unto Him for the uncountable blessings that He caringly and providentially provides to us all (Romans 1:18-25; Acts 14:17; Daniel 5:23; Psalm 14:1).

Meanwhile, speaking of giving thanks, Thanksgiving is fast approaching; many folks are thinking about the American Turkey. See “Strangers and Pilgrims (and the American Turkey)”, posted at https://leesbird.com/2014/11/25/strangers-and-pilgrims/ .

HighlansCenter.org / Felipe Guerrero photo credit

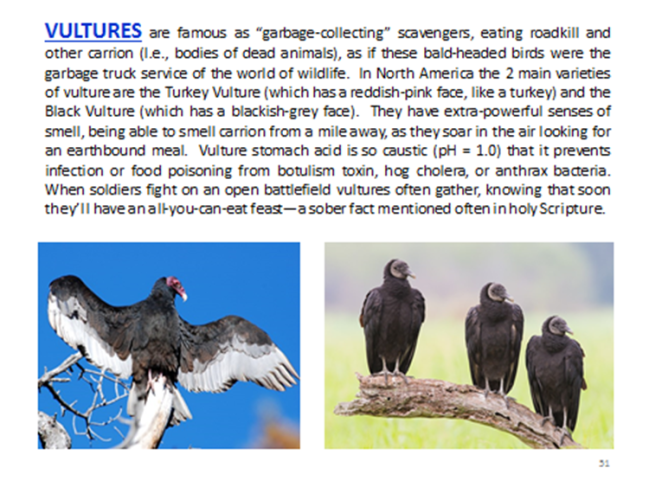

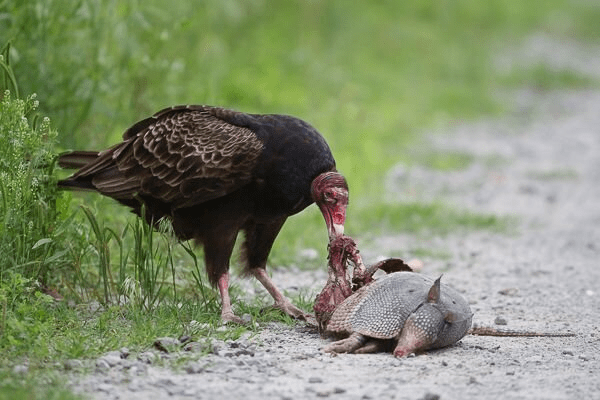

But what about another large bird that we often see, the Turkey Vulture? This scavenger, known scientifically as Cathartes aura, is actually a very valuable neighbor in whatever habitat they inhabit.

Turkey vultures are most interesting creatures. One can tell, just by looking at them, that they are well-suited to their task as disposers of dead things. Their beaks and feet lack the power and the design for killing living things, though their hooked beaks allow them to free the last shred of meat clinging to a carcass. Their heads are completely featherless, which makes it easier to clean them of bacteria and parasites encountered while rooting around in dead carcasses. Turkey vultures nest on crags, caves and clefts in rock piles. They don’t bother to build a nest. The female lays her two brown, mottled eggs on the bare ground and incubates them for forty-one days. When the babies hatch, they are fed exclusively on a diet of regurgitated carrion. (Yumm!??) These birds sound totally disgusting, right? Actually, they are quite impressive. They are a very large bird—males and females are quite similar in appearance, with shiny black feathers. They have a wingspan of up to six feet, and the underside tips of their flying feathers are greyish white. When they are observed soaring aloft on the thermals, they are quite beautiful indeed, and beauty is in the eye of the beholder. [Quoting Sandy Stoecker, Highlands Center for Natural History naturalist]

But, how did the Turkey Vulture get its valuable role in the so-called “circle of life” neighborhood (i.e., within the dynamic life-and-death ecosystem of this fallen (i.e., good-yet-“groaning”-with-sin and-death) world? The fallenness of our world is thanks to Adam (Romans 5:12-21); however, the gift of life–from the beginning–plus the providential and redemptive sustaining of life in this fallen world–is thanks to our Lord Jesus Christ, Who is both the life-giving Creator (John 1; Colossians 1; Hebrews 1) and the life-restoring Redeemer (Romans chapter 8, especially Romans 8:21-23).

Because the creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travails in pain together until now. And not only they, but ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the redemption of our body. (Romans 8:21-23)

Wikipedia / Peter Burian photo credit

It’s not by good luck that turkey vultures can find rotten carrion, gobble it down, and not die of food poisoning. Vultures have powerful senses of sight and smell; they detect dead animals from afar. Equipped by God for scavenging in this fallen world, they serve as garbage collectors/processors, picking apart and eating roadkill and other carcasses.

Why don’t they get sick or die of botulism? The acidity of vultures’ digestive tracts is astounding. The digestive juices in their stomachs can reach a pH between 1.5 and 1.0, more corrosive than car battery acid and caustic enough to instantly denature to death almost any bacterial or viral pathogen! [Chen, Y. et al. 2023. Vultures as a Model for Testing Molecular Adaptations of Dietary Specialization in Birds. Avian Research. 14: 100128; Buechley, E. R. and C. H. Sekercioglu. 2016. Vultures. Current Biology. 26 (13): R560–R561. Genesis 15:11 reports on carrion-seeking birds whose behavior resembles that of vultures.]

Wikipedia / Charles J. Sharp photo credit

In other words, if the vultures’ Creator had not constructed their stomachs with such germ-destroying acidity, the vultures themselves would quickly become dead meat. These built-in (and interactively dynamic) habitat-fitting traits utilize what Dr. Randy Guliuzza calls “continuous environmental tracking”, linked to providentially installed equipment that adjust to the outside world that the vultures live in. God’s providence is thus obvious to — and logically recognized by — honest observers, because God’s glorious craftsmanship is what the apostle Paul calls “clearly seen” (Romans 1:20).

For in-depth analysis of these providential bioengineering wonders (illustrated by God’s amazing creatures), see Dr. Randy Guliuzza’s series on Exploring Adaptation from an Engineering Perspective, posted (e.g.) at http://www.icr.org/article/exploring-adaptation-from-engineering-perspective//1000 — which introduces the truth-seeking reader to Dr. Guliuzza’s series, posted at http://www.icr.org/home?f_search_type=icr&f_keyword_all=&f_keyword_exact=Engineered+Adaptability&f_keyword_any=&f_keyword_without=&f_search_type=articles&f_articles_date_begin=5%2F1%2F2017&f_articles_date_end=12%2F31%2F2019&f_authorID=203&f_typeID=11§ion=0&f_constraint=both&f_context_all=any&f_context_exact=any&f_context_any=any&f_context_without=any&module=home&action=submitsearch .

Sound View Camp photo credit

Meanwhile, it’s sad that arrogant evolutionists, like Joel Duff, are self-blinded to these clearly seen Christ-honoring wildlife ecology facts, but they show themselves as self-blinded, habitually, “without excuse” [αναπολογητους] — see Romans 1:18-25 (especially Romans 1:20.)

But, for those with eyes to see it, we can enjoy God’s brilliant bioengineering displayed in Turkey Vultures — and also in the American Turkey — as we approach Thanksgiving with an attitude of gratitude.

.jpeg.aspx?width=762)