SEED-LOVING BOBOLINKS, GROUND-NESTING IN GRASSLANDS

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

If a bird’s nest chance to be before thee in the way in any tree, or on the ground, whether they be young ones, or eggs, and the mother sitting upon the young, or upon the eggs, thou shalt not take the mother with the young.

(Deuteronomy 22:6)

Moses noted that some wild birds build their nests upon the ground; Bobolinks do just that.

Years ago, I reported on the Black-capped Chickadee, noting that I first saw one at Gilsland Farm Sanctuary, while attending a wetland ecologists’ meeting: “Decades ago, I saw Black-capped Chickadees, for the first time, in Falmouth (near Portland), Maine – at the Gilsland Farm Sanctuary (now called “Gilsland Farm Audubon Center”), on May 31st of AD1995, while attending the annual national meeting of the Society of Wetlands Scientists.” [Quoting from “Tiny Yet Tough: Chickadees Hunker Down for Winter”, posted at https://leesbird.com/2016/11/18/tiny-yet-tough-chickadees-hunker-down-for-winter/ .]

Another “lifer” that I then observed that day, at Gilsland Farm Sanctuary, was the BOBOLINK. And what a striking plumage the male Bobolink has, during breeding season!

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Bobolinks (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) are icterids (blackbirds of the Western Hemisphere), dwelling in America’s prairie and pasture grasslands and marshy wetlands during the warm months of the year. Bobolinks were nicknamed “rice birds” (which matches their species name, oryzivorus, meaning “rice-eating”), due to their dining habits, especially during autumn migrations.

The Bobolink genus name, Dolichonyx, means “long claw”, matching its prehensile perching “fingers”.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

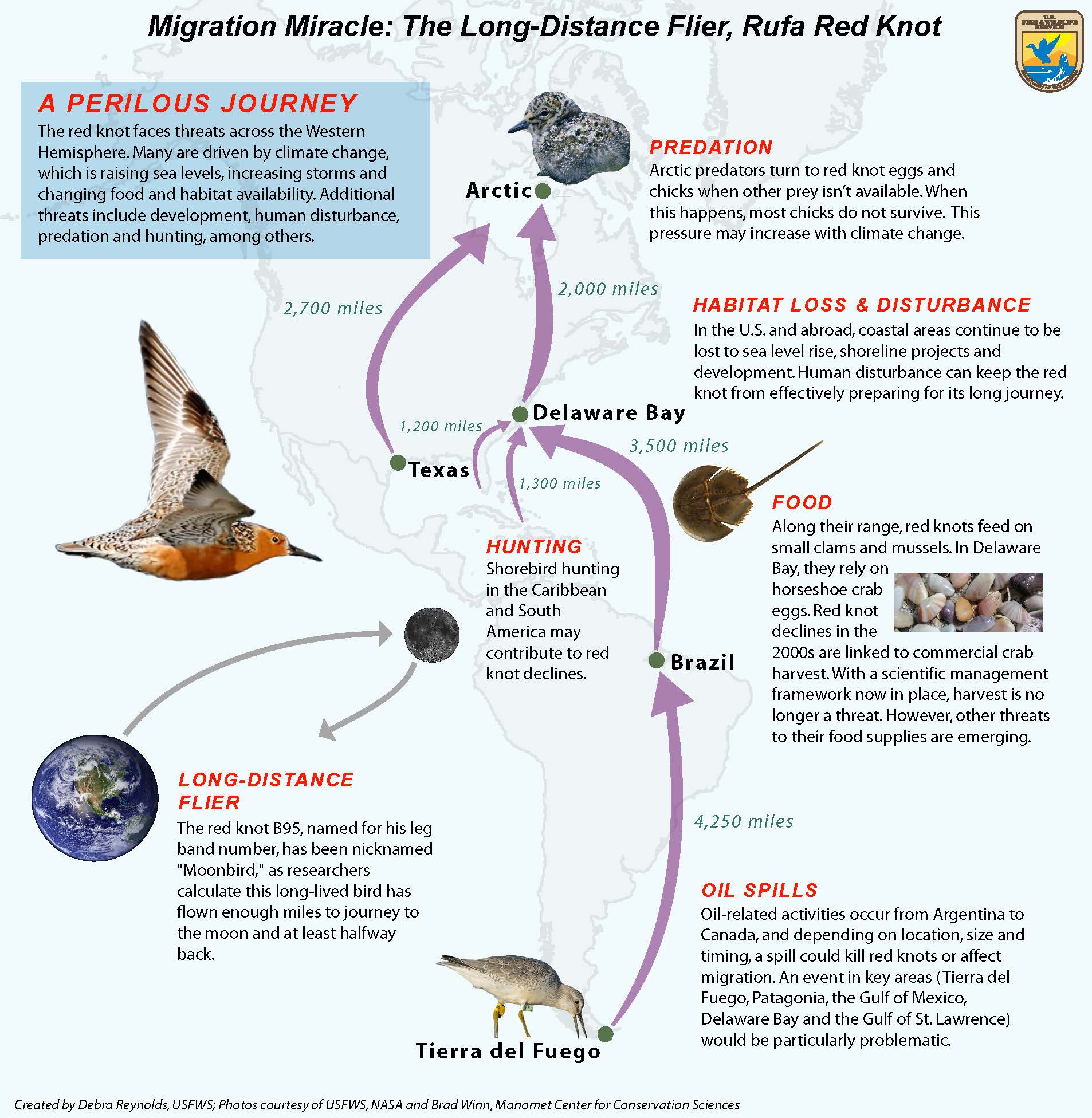

During such migrations Bobolinks frequently feed in farmed fields of rice and other grains (such as oats, sorghum, maize corn, and hayseed), at energy-packing refueling stopovers (e.g., in South Carolina and the Gulf states), on their aerial journeys southward, via Caribbean islands, en route to South American over-wintering range destinations.

Bobolinks feed on (or near) the ground, eating various seeds, insects, spiders, and even snails—especially during breeding seasons. Both larvae and adults of insects (especially armyworm moths) are protein-rich, much needed for growing Bobolink juveniles.

Also, during breeding seasons, Bobolinks depend upon available hay for nest-building, on the ground, in vegetated areas.

Bobolinks are quite specific in their breeding habitat needs. Open hay fields are a must, and so as farming is some regions of the country diminishes, so do populations of bobolinks. Where colonies of bobolinks have traditionally bred, it is important to preserve their habitat with regular mowing practices. Unfortunately, the right time to mow a field for hay is often just when the young are fledging[!]. Careful observation of the behavior of a [bobolink] colony and delaying of mowing until one or two weeks after fledging, a time when the young can fly fairly well, will keep a colony producing and ensure its [multi-generational] survival.

[Quoting Donald W. Stokes & Lillian Q. Stokes, A GUIDE TO BIRD BEHAVIOR, Volume III (Boston: Little, Brown & Company/Stokes Nature Guides, 1989), pages 351-352.]

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Consequently, Bobolinks are easier to find in habitats where their needs for food and nesting are plentiful.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

The males have easily seen plumages—like reverse tuxedos (white upon black) in spring and summer, during breeding months.

(photo credit: Bryce Gaudian)

Male and female bobolinks are easily distinguished during the breeding season. Males have a black head, belly, and wings, with a buff-gold nape and white patches on the back. The female is buff [and brown] colored all over with dark streaks on her back, wings, and sides.

[Quoting Donald W. Stokes & Lillian Q. Stokes, A GUIDE TO BIRD BEHAVIOR, Volume III (Boston: Little, Brown & Company/Stokes Nature Guides, 1989), pages 364.]

During non-breeding months, however, Bobolink males shift to duller hues of dark and light browns, similar to the year-round plumage of Bobolink females and juveniles.

(Mircea Costina / Shutterstock / ABCbirds.org photo credit)

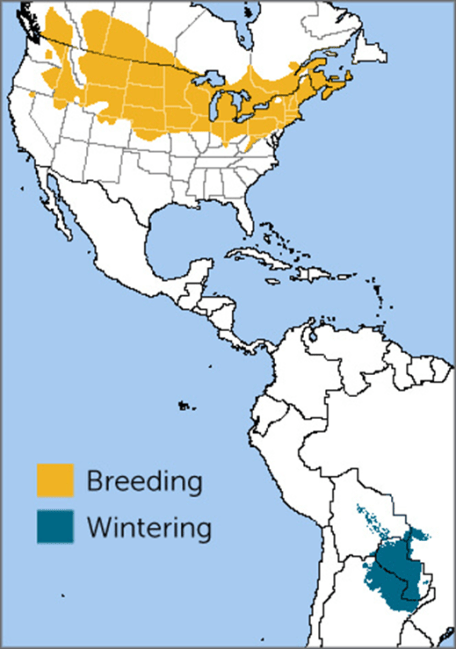

Of course, these tweety-chirpy icterids breed elsewhere in spring – in most of the upper half of America’s Lower 48, from the Northeast’s coastlines almost as far wet as the coasts of Washington and Oregon. Accordingly, the Bobolink migrates about 6,000 miles southward or northward, so it accrues about 12,000 miles per year, in air miles.

It was a privilege to see Bobolinks, back in AD1995, at the Gilsland Farm Sanctuary, as part of my time attending the Society of Wetlands Scientists’ meeting.

Likewise, it’s a privilege, now, to be permitted to share some of the wonderful Bobolink photographs taken in Minnesota, by Christian/creationist photographer BRYCE GAUDIAN — thanks, Bryce!

And now, it’s time for a limerick, about Bobolinks.

In Appreciation of the Bobolink, a/k/a Rice Bird

There’s an icterid feathered quite nice,

Whose fast-food oft includes rice;

It makes a chirp-sound,

As it nests on the ground,

And it’s photo’d quite well, by Bryce!