Dr. James J. S. Johnson

But if any provide not for his own, and specially for those of his own house, he hath denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel. (1st Timothy 5:8)

There she was, that shameful sneak! An unmotherly and irresponsible female Brown-headed Cowbird!

(National Audubon Society photo credit)

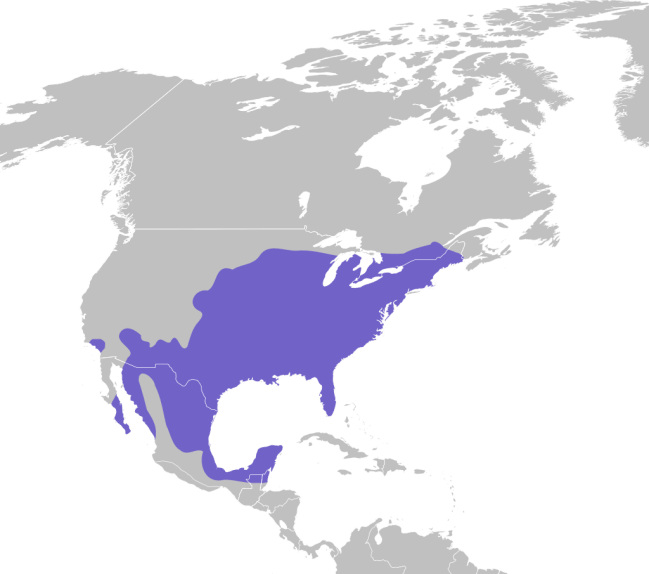

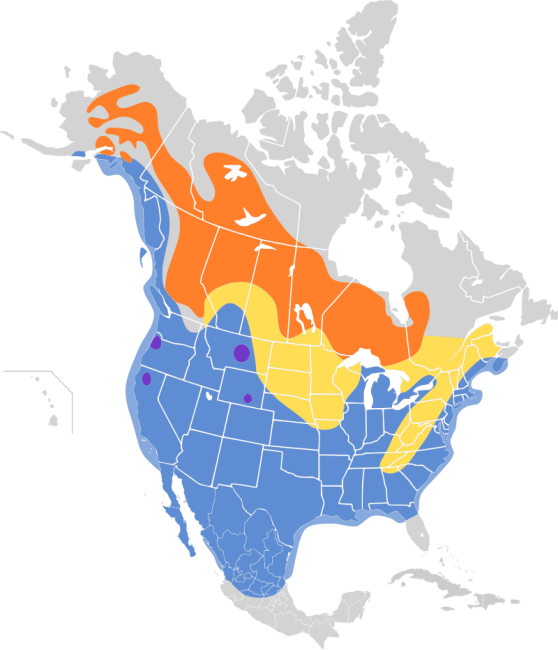

Why do I say “sneak”? Because the female Brown-headed Cowbird is the most prominent example of a “brood parasite” in North America. Cowbird mothers refuse to raise their own young; they use deceit to “dump” their kids on other mothers (and fathers) to raise. Shame on them! In fact, about half of America’s Lower 48 states are year-round residence range for these brood-parasitic icterids.

In other words, the mother cowbirds sneakily deposit their eggs into the nests of other bird mothers – so that the involuntary “foster mothers” are left with the responsibility of raising the cowbird hatchlings. The ornithologists at Cornell University describe the cowbird mother’s habits:

The Brown-headed Cowbird is North America’s most common “brood parasite.” A female cowbird makes no nest of her own, but instead lays her eggs in the nests of other bird species, who then raise the young cowbirds. …

Brown-headed Cowbird lay eggs in the nests of more than 220 species of birds. Recent genetic analyses have shown that most individual females specialize on one particular host species. …

Cowbird eggs hatch faster than other species eggs, giving cowbird nestlings a head start in getting food from the parents. Young cowbirds also develop at a faster pace than their nest mates, and they sometimes toss out eggs and young nestlings or smother them in the bottom of the nest. [Quoting “Brown-headed Cowbird: overview”, posted on Cornell Lab’s AllAboutBirds.org website]

(Wikipedia photo credit)

In other words, unlike the noble stepparent, who intentionally and unselfishly accepts the child-rearing responsibility for a (typically ungrateful) child who was procreated by someone else, avian “foster parents” who raise undocumented alien offspring (of Brown-headed Cowbirds) do so unawares.

(Everyday Cinematic Birds / YouTube photo credit)

Of course, not all nest-managing birds are fooled by brood parasite birds — regarding Australia’s Superb Fairywren, who uses a parental “password” to vet her nestlings for legitimacy, see “Pushy Parasites and Parental Passwords“, posted at http://www.icr.org/article/pushy-parasites-parental-passwords .

Also, the statistical prospects for cowbird babies is unimpressive: out of about 40 eggs laid/abandoned per year, by cowbird mothers, only about 2 or 3 survive to adult maturity. [See Donald Stokes & Lillian Stokes, “Brown-headed Cowbird”, A GUIDE TO BIRD BEHAVIOR, Volume II (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, & Company), page 213.)

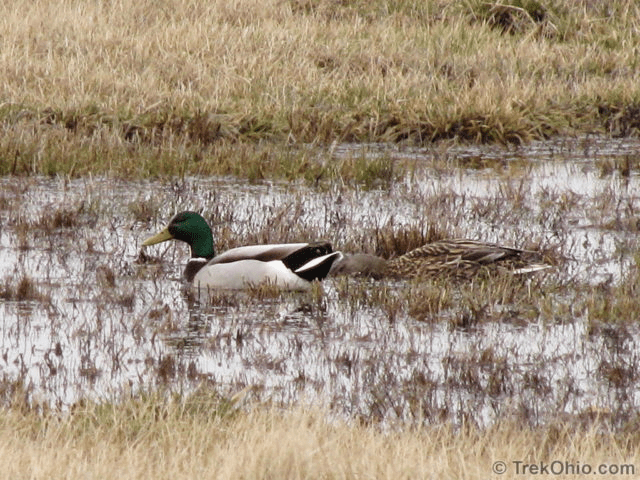

Earlier this month, enjoying fair weather, I went birdwatching with my son, in some suburban parks of Dayton (Ohio).

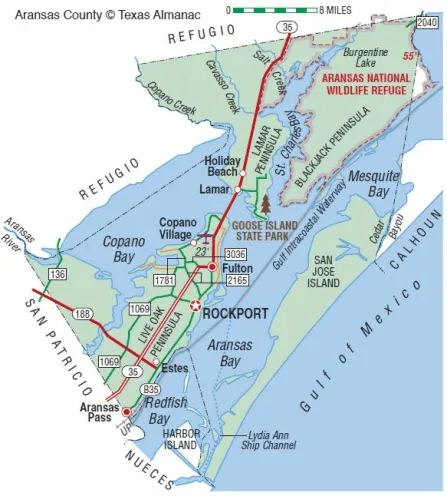

(TripAdvisor photo credit)

One of the best birdwatching venues is Cox Arboretum MetroPark, a 174-acre botanical preserve with many forested hiking trails [see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cox_Arboretum_and_Gardens_MetroPark ].

The above-noted birdwatching experience was enhanced by my son’s smart-phone’s usage of an “app” called MERLIN (Merlin Bird ID, by Cornell Lab: https://merlin.allaboutbirds.org ) which identifies (by name) bird calls, plus provides a color photograph, when a bird’s calls are recognized by the app. Most of the recognized birdsongs were from American Robins or various sparrows (e.g., Chipping Sparrow, English Sparrow, etc.), but more than once the songbird was a female Brown-headed Cowbird.

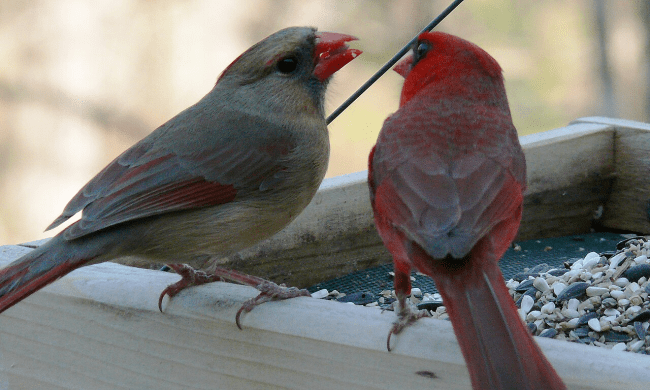

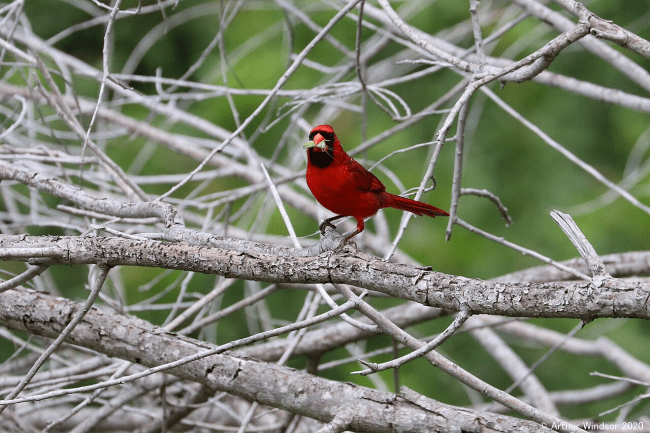

Of course, male Brown-headed Cowbirds are easy to recognize, as shown below.

(Wikipedia photo credit)

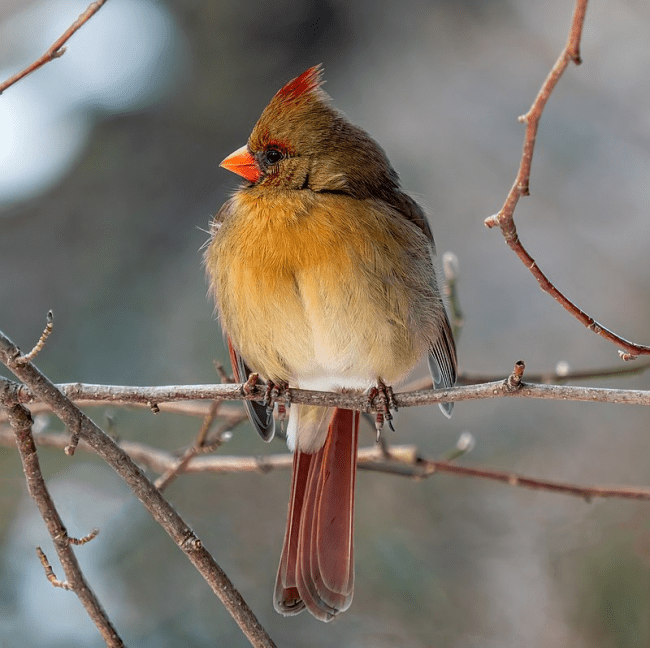

However, female Brown-headed Cowbirds are much less conspicuous in plumage, because the soft-brown-hued females do not have shiny iridescent plumage that make males so easily recognizable.

(Wikipedia photo credit)

The Cornell Lab’s Merlin app also identifies birds visually – you just “zoom [in] until your bird fills the box” (on your smart-phone), then the Merlin app identifies the bird, plus it supplies some basic information about the bird that you are photographing on your smart-phone. Nice!

There’s even more features to the Merlin app – but this is enough to suggest its usage. In other words, the main point (of this blogpost) is simple enough: get out there, and appreciate God’s Creatorship as you do some birding!