Cormorants are Great; Great Cormorants are Really Great!

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

“But the cormorant [shalak] and the bittern shall possess it [i.e., the land of Idumea, a/k/a Edom]; the owl also and the raven shall dwell in it; and He [i.e., the LORD, in judgment] shall stretch out upon it the line of confusion, and the stones of emptiness.“

Isaiah 34:11

photo credit: Bryce Gaudian

In some contexts, CORMORANTS are not deemed as indicators of blessing — as in Isaiah 34;11, where it is prophetically mentioned as an indicator that the land of Edom is catastrophically destroyed. However, in many other contexts, these magnificent birds are recognized as wonderful creatures whom God has equipped to live by bodies of water, both freshwater and seawater.

photo credit: Bryce Gaudian

Cormorants love to live by bodies of water. Cormorants are found busy hunting — darting (befitting the Hebrew noun shalak, in Leviticus 11:17 & Deuteronomy 14:17, translated “cormorant”, which matches the darting-like targeting movements) for food over and near coastlines, including the coasts of islands, such as the Hebridean isle of Staffa, which was reported earlier (on this Christian birdwatching blog), in the report titled “Birdwatching at Staffa: Puffins, Shags, and more”, posted at https://leesbird.com/2019/07/22/birdwatching-at-staffa-puffins-shags-more/ (July 22nd A.D.2019), citing Isaiah 42:12. [Regarding “cormorants” in the Holy Bible, see George S. Cansdale, ALL THE ANIMALS OF THE BIBLE LANDS (Zondervan, 1976), at page 175.]

Cormorants constitute a large “family” of birds; the mix of “cousins” include Crowned Cormorant (Phalacrocorax coronatus), Brandt’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax penicillatus), Galapagos Cormorant (Phalacrocorax harrisi), Bank Cormorant (Phalacrocorax neglectus), Neo-tropic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax brasilianus), Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), Indian Cormorant Phalacrocorax fuscicollis), Socotra Cormorant (Phalacrocorax nigrogularis), Cape Cormorant (Phalacrocorax capensis), Guanay Cormorant (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii, a/k/a Guanay Shag), Kerguelen Shag (Phalacrocorax verrucosus), Imperial Shag (Phalacrocorax atriceps), Antarctic Shag (Phalacrocorax bransfieldensis). South Georgia Shag (Phalacrocorax georgianus), Campbell Island Shag (Phalacrocorax campbelli), New Zealand King Shag (Phalacrocorax carunculatus), Bronze Shag (Phalacrocorax chalconous), Chatham Island Shag (Phalacrocorax onslowi), Auckland Island Shag (Phalacrocorax colensoi), Rock Shag (Phalacrocorax magellanicus), Bounty Island Shag (Phalacrocorax ranfurlyi), Red-faced Cormorant (Phalacrocorax urile, a/k/a Red-faced Shag), European Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis), Pelagic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus, a/k/a Pelagic Shag), Red-legged Cormorant (Phalacrocorax gaimardi), Spotted Shag (Phalacrocorax punctatus), Pied Cormorant (Phalacrocorax varius), Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo), Japanese Cormorant (Phalacrocorax capillatus), Olivaceous Cormorant (Phalacrocorax olivaceus, a/k/a Mexican Cormorant), and Pitt Island Shag (Phalacrocorax featherstoni).

That’s a lot of cormorant “cousins”, worldwide! [For details on each of these “cousins”, see pages 116-136 of Jim Enticott & David Tipling, SEABIRDS OF THE WORLD: THE COMPLETE REFERENCE (Stackpole Books, 1997).]

Notice: Cormorants are not anhingas!

To distinguish these 2 large black fish-loving birds, see “Of Cormorants and Anhingas” (June 13th A.D.2019), posted at https://leesbird.com/2019/06/13/of-cormorants-and-anhingas/ .

photo credit: Public Insta

Cormorants are famous “fishermen” along ocean coastlines, yet cormorants also thrive in inland freshwater habitats, such as over and near ponds and lakes, such as the Double-crested Cormorants that frequent inland ponds in Denton County, Texas, where they catch “fish of the day”.

photo credit: Bruce J. Robinson

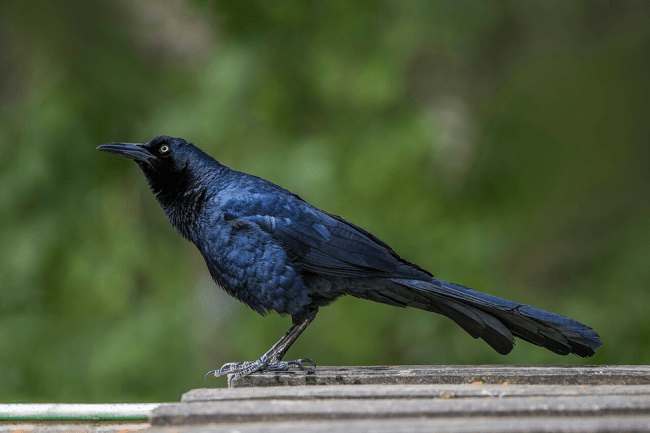

Cormorants are generally described, by ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson, as follows:

Large, blackish, slender-billed water birds. Often confused with loons, but tail longer, bill hook-tipped. In flight, wing action is more rapid and axis of body and neck is tilted upward slightly (loon’s neck droops). Young birds are browner, with a pale or whitish breast. Flocks [of cormorants] fly in line or wedge formation very much like geese but they are silent. Cormorants often perch in upright positions on buoys or posts with neck in an S [posture]; sometimes strike a “spread eagle” pose. Swimming, they lie low like loons, but with necks more erect and snakelike, and bills tilted upward at an angle. Food: Fish (chiefly non-game). Nearly cosmopolitan [in range].

[Quoting Roger Tory Peterson, cited below]

[See Roger Tory Peterson, A FIELD GUIDE TO THE BIRDS OF TEXAS AND ADJACENT STATES (Houghton Mifflin, 1988), page 10.]

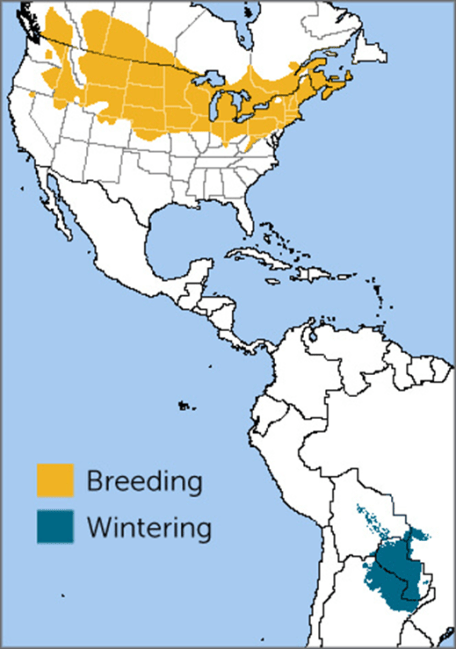

Specifically, the Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritis) is perhaps the most common winter migrant of the cormorants; also, the Double-crested Cormorant is often seen in the coastline areas of Texas’ Gulf of Mexico shores.

photo credit: Bryce Gaudian

Have you ever watching a silhouetted cormorant — or two — or three — winging their way across the late afternoon sky? It is a wonder to behold!

photo credit: Bryce Gaudian

Now, try to imagine a dozen, or more, cormorants, flying in series. That’s a wondrous wonder to behold! That constitutes one of the “wonders without number” that Scripture refers to (in Job 9:10).

photo credit: Bryce Gaudian

And now here is my closing limerick, about cormorants:

APPRECIATING HUMBLE CORMORANTS (AND SHAGS)

Cormorants are not known to brag,

If they’re so-called, or called “shag”;

They oft fly, in a line,

And on fish, they oft dine —

But cormorants aren’t known to brag.

photo credit: Mark Eising Birding

(Dr. Jim Johnson formerly taught ornithology and avian conservation at Dallas Christian College, among other subjects, and he has served as a naturalist-historian guest lecturer aboard 9 international cruise ships, some of which sailed in seawaters frequented by cormorants and shags. Jim was introduced to Christian birdwatching as an 8-year-old, by his godly 2nd grade teacher, Mrs. Thelma Bumgardner.)