GO, FLY — A KITE!

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

And the vulture, and the kite after his kind…. (Leviticus 11:14)

And the glede, and the kite, and the vulture after his kind …. (Deuteronomy 14:13)

Flies (and other flying insects) better flee, whenever a hungry Mississippi Kite flies by!

Perhaps the term “kite”, translating the Hebrew noun אַיָּה [’ayyâh] in Leviticus 11:14, and in Deuteronomy 14:13, refers to the Black Kite (Milvus migrans) that currently dwells in the Holy Land – as well as in several parts of Eurasia, Australia, and Africa.

Once, recently, while I was gazing at tree-perching cardinals and mockingbirds, a Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis) landed on a tree-branch near my house, recently (Wednesday, May 7th, A.D.2025), letting me to see its magnificent movements and eye-catching plumage.

During springtime, here in North Texas, local insect populations are booming – and this busy bonanza is an insectivore’s smörgåsbord for Mississippi Kites, who love to eat flying and crawling insects (bees, cicadas, dragonflies, grasshoppers, and more!).

Also, these diurnal raptors (i.e., daytime hunters) employ their short hooked beaks to eat other small animals, e.g., small snakes, lizards, frogs, mice, bats, and even small birds. If cicadas are abundant, as they periodically are, kites may feast on them beyond other foods. [See Stan Tekiela, “Mississippi Kite”, BIRDS OF TEXAS FIELD GUIDE (Adventure Publications, 2020), pages 326-327.]

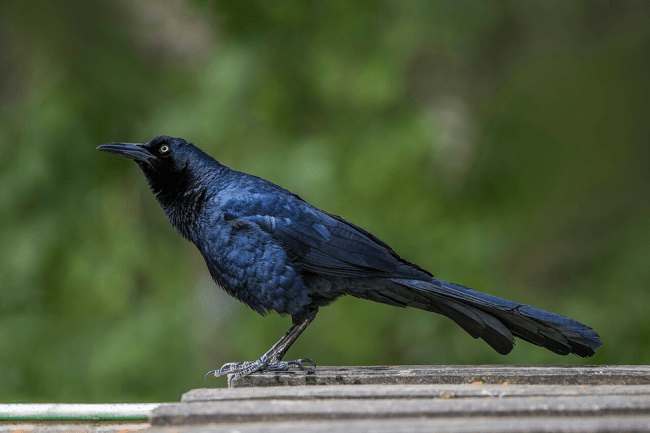

This mostly grey-colored maneuvering marvel has a black tail, dark-red eyes (surrounded by black “blackeye-like eyepatches), red-to-yellow legs, charcoal-grey (with some russet-brown) plumage on the wings, and whitish-grey “ashy” underside and head; the kite’s head is such a pale grey that it is almost white, similar to a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher’s head. It is easy to remember a Mississippi Kite when you see one – what a beautifully bioengineered and impeccably constructed bird it is!

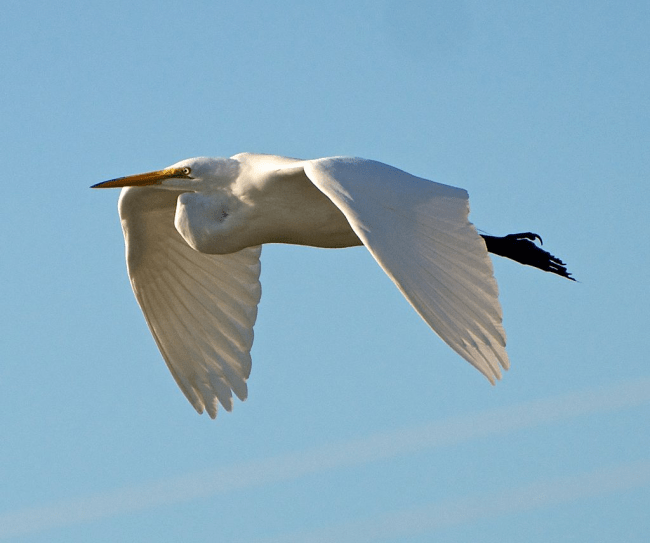

(Ozark Bill Duncan photo credit)

In fact, the Mississippi Ornithological Society (which, as its name indicates, is an ornithological society that focuses on Mississippi birds) has named its semiannual journal for this marvelous bird (see https://missbird.org/kite/ ).

Smaller than eagles, vultures, and most hawks, these aerial acrobats are migratory accipiters, i.e., smaller hawks with short, broad wings, plus relatively long legs (with precision-designed talons!), often found flying fastly in wooded habitats that include riparian edges. Since my neighborhood has several ponds and drainage ditches, it’s no surprise that kites visit occasionally – this is not the first time that I’ve seen a kite on my homeplace.

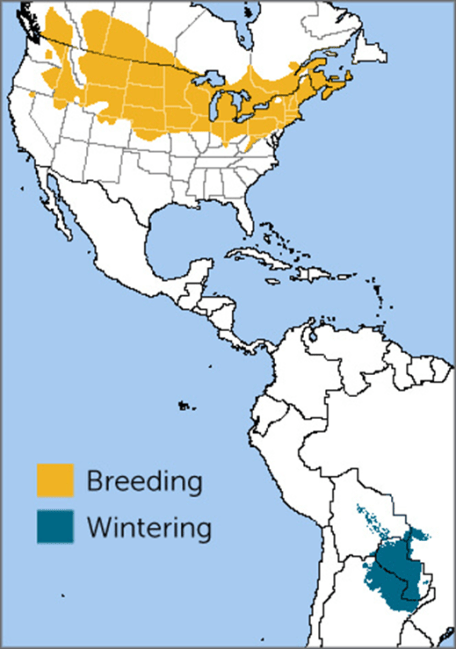

Unsurprisingly, this Mississippi Kite visited my Texas homestead in springtime. These kites routinely winter in Central or South America, yet sometimes they winter within the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas. During spring they migrate northward, to their summer nesting-and-breeding grounds; besides Mississippi (where they are famous for dwelling near the Mississippi River), they migrate to breeding ranges north of Mexico, including Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, and much of northern Texas. Some are even known to have migrated as far north as South Dakota, or as far east as Florida! [See, accord, David E. Fantina, “Mississippi Kite”, THE TEXAS BREEDING BIRD ATLAS (posted at Texas A&M AgriLife Research, at https://txtbba.tamu.edu/species-accounts/mississippi-kite/ .]

According to Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, kites are social creatures:

Mississippi kites are very social in all activities. They do not maintain territories and they congregate at roosts in late summer. . . . . Kites have been known to fly about cattle and horsemen in order to catch insects that are stirred up from the grass [acting as the airborne equivalent to pasture-strolling Cattle Egrets!].. . . .

Paired kites generally begin nesting soon after their arrival in their old nests or in newly constructed ones. In late May or early June, kites breed and both sexes will incubate usually two bluish-white eggs until they hatch 31 to 32 days later.

Mississippi kites, at times, cause problems for unsuspecting individuals. Kites, like many other birds, will dive at animals and people that venture too closely to their nests. This diving behavior is simply an attempt to ward off potential threats to the nest and young. Once the young leave the nest some 30 to 34 days after hatching, kites will stop their protective behavior. Kites normally may live to seven years of age in the wild.

[Quoting TP&WD, https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/species/kites/ .]

(Jeff Tibbits / Oklahoma Dep’t of Wildlife Conservation photo credit)

Kites are a lot like falcons, they are small birds of prey with streamlined and quick-darting maneuverability in flight. They prefer to nest in habitats of tall trees – “near water, in open woodlands, savannahs, and rangelands … [and sometimes] in urban settings” – according to Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (see https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/species/kites/ ).

What an unexpected privilege it was, a few days ago, when I spotted that Mississippi Kite landing upon that tree-branch – perhaps that tree had some insects that the kite spotted, and quickly consumed. In any case, it’s a beautiful bird to which God gave admirable mobility.

(Vincent Fouchi, Jr. photo credit)

So, here is a limerick to remind us of how the Mississippi Kite is an aerial hunter of insects:

MISSISSIPPI KITE, AERIAL HUNTER OF INSECTS

Eyes dark red, and head greyish-white,

Pointed wings, for quick-turning flight —

Its curled beak grabs a bee;

Insects, you better flee!

Beware the Mississippi Kite!

:)