Birdwatching in Iceland

by James J. S. Johnson

The Lord reigneth; let the earth rejoice; let the multitude of isles be glad thereof. (Psalm 97:1)

Islanders, like others, should rejoice in appreciation for the historic incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ – which incarnation we celebrate annually as Christmas. It is that same Christ (John 1:1-3; Hebrews 1:1-3) Who made all the seabirds that visit and live on the world’s islands, and Iceland is no exception.

Orni-Theology

A recent email from Iceland reminded me of some birdwatching, years ago, that my wife and I did, while visiting Iceland. Some might think that a place called “Iceland” would be so cold that birds, there, would be few and far between. Thankfully, that is not the case, especially due to the moderating influence of the warm Gulf Stream current, which washes the southwestern shores of Iceland. The birds of Iceland, like those of many other islands, are (unsurprisingly), are predominantly waterbirds, since islands are surrounded by water, typically ocean water.

What were some of the birds that my wife and I saw, then (September 17th of AD2002), in Iceland? A few examples are mentioned below, with special attention to Icelandic geese and swans (which is especially relevant to the sequel to this birdwatching report, which will report on a Bohemian goose and a Saxon swan).

Waterbirds live around (and sometimes in) bodies of water, sometimes saltwater and sometimes freshwater. Waterbirds might habituate seacoasts, riverbanks, estuarial mudflats, lakes, ponds, swamps, and water-logged marshlands. (Some are attracted to manmade water bodies, such as dam reservoirs, concrete canals, swimming pools, fountains, or birdbaths.) Birds need water.

Think of the various waterbird categories, some wading shorebirds, some seabirds: goose, gull, grebe, gallinule, gannet, guillemot, limpkin, loon, duck, dipper, brant, booby, bittern, coot, crane, crake, curlew, cormorant, kittiwake, kingfisher, plover, pelican, puffin, penguin, petrel, phalarope, flamingo, fulmar, frigatebird, albatross, anhinga, auklet, ibis, eider, egret, oystercatcher, osprey, mallard, merganser, murre, shag, shearwater, shoveler, smew, spoonbill, stint, stork, scoter, scaup, skua, skimmer, swan, sandpiper, sora, snipe, wigeon, tern, teal, tropicbird, turnstone, jabiru, jaeger, jacana, heron, knot, noddy, rail, redshank, — the list could go on and on!

SeaGulls on Railing, by James J. S. Johnson

Seagulls.

Seagulls — such as gulls, terns, and fulmars — are one of the most typical kinds of seabirds. For example, see the Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus), perching on the railing of the Royal Caribbean cruise ship (Jewel of the Seas), which I photographed as the ship approached the harbor of Helsinki, Sweden, during the summer of AD2006.

Ironically, many “seagulls”, such as herring gulls and ring-billed gulls, are observed far from the “sea”, living inland as residents or migrants, at huge distances many miles away from the closest saltwater shoreline. For example, during winter the Ring-billed gull (Larus delawarensis) is known to congregate in the parking lots of shopping centers near Dallas, hardly a “range” fit for a “seagull”! However, visiting a saltwater beach, like the Gulf of Mexico or an ocean, provides opportunities for seeing many kinds of seagulls, at any time of the year.

While serving as a speaker on a cruise ship, during September of AD2002, the ship headed from Ireland’s Dublin to Iceland’s Reykjavik. Along the way I saw a variety of seagulls, including: Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), on a boat-dock in Dublin; Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis), in a Dublin estuary; Storm Petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), over the Irish Sea just north of Dublin; Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), at sea somewhere between Scotland and Iceland; Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), also at sea somewhere between Scotland and Iceland; Black-headed Gull (Larus ridibundus) and Lesser Black-headed Gull (Larus fuscus), both of which I saw in the open sea somewhere between Scotland and Iceland. In time our boat docked at Reykjavik (Iceland), where I would happily see some “lifers” (and other birds I’d seen before).

Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus). Near the Reykjavik dock there was a rocky shoreline where a colony of busy Manx Shearwaters could be seen, apparently not far from their summer nests in rocky crevices. These are seabirds are sooty black on top and white underneath, except for a white bar on the upper side of their underwings. These low-flying birds are pelagic (staying at sea most of the time), often accustomed to following boats, coming to shore at sunset to breed. Their diet includes fish, aquatic crustaceans, carrion, and whatever seafaring humans dump or throw overboard (i.e., human garbage or donated food-scraps).

Manx Shearwater

Arctic Skua (Stercorarius parasiticus). One of the tourist stops in Iceland is the world-famous geyser named Geysir – this is the namesake of all geysers, translating literally as “gusher”. (Iceland has been volcanically active for more than 1000 years, so geysers, fumaroles, and volcanic lava-flows are always foreseeable there.) Like Yellowstone’s “Old Faithful”, this famous geyser has lost power over the centuries, but it is still an impressive hydrothermal spring that intermittently expels boiling hot mineral waters from its surface vent. Near the gushing geyser Geysir, I saw Arctic Skua, a seabird that often frequents boggy tundra fields, especially damps heathland areas alogn island coastlands. [See Jürgen Nicolai, Detlef Singer, & Konrad Wothe, Birds of Britain and Europe (Collin Nature Guides, 2000; trans. By Ian Dawson) at page 122.] The Arctic Skua is rather aggressive, robbing other birds of their fish, and sometimes taking their nest eggs; skuas are also know to eats small rodents, such as mice. This skua is brown-winged, brown-legged, and brown-capped, but is otherwise mostly white, resembling a Common Gull in size and body shape, except its dark brown tail feather assembly has two pointed projections. If seen closely some yellowish tint accents its neck and cheeks. It is usually at sea except during the breeding season (May to July).

Arctic Skua

Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides). Near Reykjavik, at the edge of a pond, a group of Iceland Gulls were loitering about. The Iceland Gull is not bashful about human settlements. This gull often “winters” at fishing boat harbors, manmade reservoirs, or coastal waste dumps. Like other gulls (including the Glaucous Gull mentioned below), the Iceland Gull is a resourceful scavenger of fish waste and other human food-scraps. This gull has plumage similar to that of the Glaucous Gull (described below) except smaller and less robust in shape, thinner, with narrower wings.

Glaucous Gull

Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus). “Flying busily about the bay-waters of Reykjavik were a group of Glaucous Gulls, whose habitats and dietary habits resemble those of the Iceland Gull (noted above). This gull is larger than most, dominated by pale white except for grey wings and back, plus freckle-like buff-hued blotches on its neck. Its legs are salmon-pink. Its bill is salmon-peach-colored except for a black tip.”

Glaucous Gulls

Ducks.

Ducks are certainly a favorite waterfowl for many. Ducks don’t limit their ranges to oceans and seacoasts; they are found (as residents or as migrants) in wetlands of all kinds, including prairie potholes, swamps, wet woods, lake, ponds, and fields watered by streams and agricultural irrigation systems.

American Wigeon flocks

In Texas’s Denton County, for years (since the early AD1990s), I have (sometimes with family, college students, and/ or other birdwatchers) enjoyed watching the behaviors of ducks that winter in our part of the Lone Star State, including (but certainly not limited to): American Wigeon (Anas americana, a/k/a “Baldpate”), a gregarious and gentle duck that frequently winter in northern Texas pond habitats; Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis, a/k/a “Bluebill”), which has a conspicuous light-blue bill; and Northern Shoveler (Anas clypeata), which is known for its extra-large shovel-shaped bill, many of which over-winter in wetlands of northern Texas. [And, as Lee Dusing recently mentioned in “Fantastic Weekend” (her birdwatching report posted at https://leesbird.com/2014/11/10/fantastic-week-end/ ), four of us Christian birdwatchers enjoyed watching a variety of palustrine and lacustrine birds, including Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris), a “lifer” for me, at Lakeland’s Morton Pond, on 11-8-AD2014.]

Ring-necked Duck male

Ring-necked Duck female

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). Near Reykjavik, at the edge of a pond, not far from a group of loitering Iceland Gulls, this famous (and far-ranged) duck was present, looking just like their cousins who inhabit northern Texas — it was like a piece of “home away from home”, to see the iridescent green heads of the mallard drakes. Mallards are not particularly shy around the habitat “edges” of human settlements, so they frequent parks and ponds, often learning that humans might provide bread crumbs or popcorn. [More on that in another posting, hopefully.]

Mallard

Mallard

Cormorants.

Earlier in this (summer AD2002) trip I had observed two kinds of cormorants. In an estuarial waterway of Dublin, 4 days before visiting Iceland, I saw Great Cormorant (Palacrocorax carbo, a/k/a “European Cormorant”) as well as Shag (Palacrocorax aristotelis, ), a smaller cormorant known for its dark-to-greenish-black hue).

Great Cormorant

Since I was concentrating of finding “lifers” I did not try to find any cormorants in Iceland. However, both of these cormorant types include Iceland in their ranges. Like me, cormorants love to eat fish. (American cormorants are often seen in manmade reservoirs, thriving on their catch of fish; of course, ocean-caught fish are more typical of cormorants, globally speaking.)

Shag

Herons, Egrets, and the like.

Because my backyard includes a pond, and that pond connects to a spill-over drainage ditch flanked by hydrophilic plants, it is not uncommon for the pond-shore to host herons and egrets.

The most frequent of these tall waders are the magnificent Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) and the majestic Great White Egret (Casmerodius albus), plus sometimes the pond is visited by the “golden-slippered” Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) or the “mustard-dabbed” Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis), plus, albeit rarely, by the clandestine Green Heron (Butorides virescens, a/k/a Butorides striatus).

Grey Heron by Ian

But the Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea) that I saw outside the city of Glasgow (Scotland), on a beach of the River Clyde (9-14-AD2002), was a “lifer” for me, so I took special notice of that particular heron. Apparently the Grey Heron is occasionally sighted in Iceland, as an “accidental” stray (i.e., rare migrant), but I did not see it or any other kind of heron.

Sandpipers, Plover, and the like.

Ringed Plover (Charadrius hiaticula) was a “lifer” for me, when I saw such on a beach of the River Clyde, outside of Glasgow (Scotland), 9-14-AD2002.

But that was Scotland, and this report of mostly about Iceland waterbirds, so without further ado I’ll report the sandpiper I saw 3 days later.

Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferrugines). The Curlew Sandpiper is a small and quite gregarious wading bird, mottled grey-brown on top and white underneath, with a conspicuously pointy bill. (During breeding the underparts change to a reddish-brown/chestnut-colored tint.)

Notice the long, thin beak. These sandpipers eat a lot of bugs and other small invertebrates (worms, leeches, snails, and mussels), often picking and probing for them on water-drained mudflats located close to arctic tundra.

Curlew Sandpiper

These migratory sandpipers are known to hybridize with other sandpipers, proving that they trace back to common ancestors who disembarked Noah’s Ark about 4½ thousand years ago. (Avian “taxonomy” is a fairly arbitrary classification scheme, so hybridizations are the real key to discovering created kinds among bird groupings.)

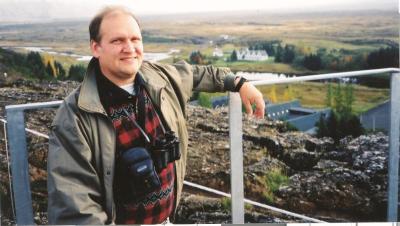

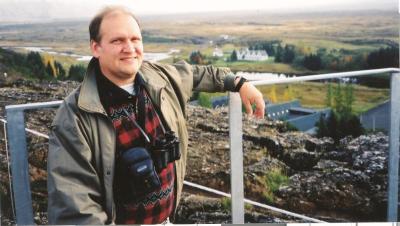

The Curlew Sandpiper was seen on the open (and slightly marshy-grassed) tundra, near the so-called “summer home” area just outside of Thingvellir [Þingvellir], historic site of the ancient Althing [Alþingi], the assembly-valley of Iceland’s parliamentary politics since AD930. [See info posted at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Althing ]. A photo of me, taken that day at Thingvellir, appears below.

Dr Jim in Iceland

Geese.

The goose that I see most frequently – sometimes a dozen congregate on the east side of my home – is the Canada Goose (Branta Canadensis). Since my neighborhood (in the “cross timbers” region of northern Texas) has several ponds, most of which are ringed by hydrophilic emergent plants, it is not surprising that these huge honking migrants winter in such places. However, in Iceland I was privileged to see some “lifers”, including four geese.

Greylag Goose with chicks

Greylag Goose (Anser anser). This “classic” wild goose has dark brown-grey feathers topside and silver-grey feathers beneath, with an orange-salmon-hued bill and pink-salmon-hued feet. Many of these geese emigrate from Iceland by or during October, not to return till late spring, so visiting Iceland during mid-September was good timing. [Lars Jonsson, Birds of Europe (Princeton University Press, 1992; translated from Swedish by David Christie), page 80.] Domesticated geese are said to derive from wild ancestors of this variety. Greylag geese habituate lakes and ponds, especially those with goose-friendly fringing wetland plants, such thick rushes and reeds. Nearby marshy meadows and pastures also attract these geese. The Greylag Geese that I saw were seen wandering about near Geysir geyser.

Greylag Goose

Pink-footed Goose (Anser brachyrhynchus). This goose was seen in mossy lava-fields by a pond outside of Reykjavik. The Pink-footed Goose prefers arctic tundra, as well as estuarial wetlands. This goose is more beige-brown than most geese, with a pink-salmon bar on its bill, pinkish feet, and a dark brown head that could be called dark chocolate (but it’s not as dark as “UPS brown”).

Pink-footed Goose (Anser brachyrhynchus)

Lesser White-fronted Goose (Anser erythropus). This goose, with a noticeable white front to its face (above its orange bill on its otherwise dark brown face), has red-gold eyes (depending upon how light shines off it), is known for eating dwarf willow grass (that grows where taiga transitions into tundra). Most of the bird’s body is covered in brown plumage, except the rump is white. This goose was spotted ambling about near a bank of the Elliðaá River just east of Reykjavik, one of Iceland’s many “salmon rivers”. [Note: this “Salmon River” is not to be confused with the more famous Lax River that runs through the Lax-dale (“salmon valley”) region of Iceland, the early pioneer history of which is chronicled in the Laxdæla Saga.]

Lesser White-fronted Goose (Anser erythropus)

Brent Goose (Branta bernicia). This relatively small-sized arctic tundra goose resembles the coloring of a White-fronted Goose (see above), except the Brent Goose has a completely brown face, plus it sports a white bar-like marking on the side of its otherwise brown neck. During winter this goose prefers mudflats providing eelgrass and algae. It was in the marshy tundra just south of Thingvellir where I saw this goose.

Brent Goose (Branta bernicia)

Swans.

The first swan I remember seeing close-up was the huge Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinators, yet a/k/a Cygynus cygnus buccinator), which can exceed 22 pounds in weight, the heaviest “native” bird of North America, considered to be a close cousin of the Eurasian Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus, noted below). These huge birds breed in southeast Alaska; when present, they are easy to see with binoculars. Another white swan, that I have seen on prior occasions, is the Tundra Swan (Cygnus columbianus), the national bird of Russia. When this swan is found in North America it is called the Whistling Swan, but many call it the Bewick’s Swan (as if it were a subspecies Cygnus columbianus bewickii, commemorating the famous bird illustrator-engraver Thomas Bewick), whenever it appears in Eurasia or Iceland. Unsurprisingly, this swan is known to habituate arctic tundra habitats.

Black Swan at Lake Morton

The Black Swan (Cygnus atratus), originally from Australia and New Zealand, has been introduced to other parts of the world (arriving sometimes in captivity as “ornamental” transplants, followed by some of the later generations escaping or being released to the wild (such as the Black Swan colony in Dawlish, Devon, in County Exeter, England), or as being “semi-released” as quasi-domesticated swans, i.e., permitted freedom to fly yet being attracted to stay by repetitive feedings (such as the Black Swan family at The Broadmoor [hotel] in Colorado Springs, Colorado — which I saw during the summer of AD2000, while I was there to present a Biblical history paper on the Moabite Stone, to the Evangelical Theological Society). As its name suggests, the Black Swan is black all over, except for a large band of white flight feathers on its wings.

Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus, pronounced “hooper”) is the “classic” white swan of Eurasia, famous for its V (“wedge”) formation when a “bevy” of these migrants are in flight, although sometimes they are seen flying in an oblique line. [Lars Jonsson, Birds of Europe (Princeton University Press, 1992; translated from Swedish by David Christie), page 76.] Besides its large white body, the Whooper Swan has a golden-yellow beak accent-tipped with black. The summer range for Whooper Swans includes Iceland, Scandinavia, Northern Russia (including Siberia), as well as tundra or taiga regions of northeastern Asia (such as Japan, northern China). The Whooper Swan is the national bird of Finland. Like other large swans, the Whooper Swan’s diet is mostly plant material (such as grasses and immature cereal grains), sometimes supplemented by some very small aquatic animals. This majestic swan was seen on a pond near the edge of Reykjavik (and was confirmed by a local Icelandic guide).

Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus)

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor). The white Mute Swan resembles the Whooper Swan (see above) in its appearance, except the Mute Swan has a conspicuous black basal “bulb” on its bill, and its bill is an orange-red hue noticeably darker than the golden-yellow bill of the Whooper Swan. Also, the Mute Swan has a black “mask” bordering its eyes and bill. Its primary food is submerged plant material. As its name suggests, it is unusually quiet for a swan, though it is known for a “hoarse hissing” when pressured into a self-defense situation. The Mute Swan is the national bird of Denmark. It was at a tundra pond near Gullfoss (“Golden Falls”) where my wife and I saw the dignified Mute Swan.

Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) by Dan

Iceland is a cool place to watch birds!

Coming soon, God willing: a sequel regarding a Bohemian goose and a Saxon swan!

Dr. James J. S. Johnson (seen here visiting Chaplain Bob Webel, a birdwatcher in St. Petersburg) believes in the God of the Bible (not in Darwin’s god-substitute labeled “natural selection”) as biodiversity’s omni-intelligent “selector”. No stranger to forensic science, Jim frequently teaches forensic evidence analysis to Texas lawyers, and is a member of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. No stranger to birds, Jim previously taught ornithology and ecology-related courses at Dallas Christian College.

*

A Bohemian Goose and a Saxon Swan (Part 2)

Orni-Theology

James J S Johnson’s Articles

*