Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

Ian’s Bird of the Week – Southern Giant-Petrel ~ by Ian Montgomery

Newsletter ~ 8/7/2013

I’ve been neglecting the bird of the week list lately, so here is a big bird and a big posting to make up. My excuse for the neglect is my recent involvement with organising a recorder workshop and the involvement of the North Queensland Recorder Society in Benjamin Britten’s opera Noye’s Fludde – Noah’s Flood – at the Australian Festival of Chamber Music in Townsville. Anyway, the musical dust is settling now and it’s back to the birds.

A Shearwater and a Petrel have featured as bird of the week recently (Providence Petrel, Flesh-footed Shearwater). They’re closely related, belonging to the family Procellariidae, so here’s one to illustrate, perhaps grossly, the difference between them. Shearwaters are slender, more elegant and have finer bills then their dumpier counterparts, the Petrels. The dumpiest of the lot is the Southern Giant-Petrel, comparable in size to the smaller Albatrosses (or Mollymawks) with a length of 85-100cm/33-39in , a wingspan of 150-210cm/59-83in and a weight of 3.8-5.0Kg/8.4-11lbs.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

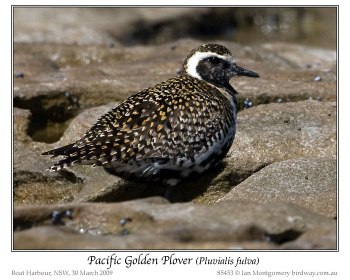

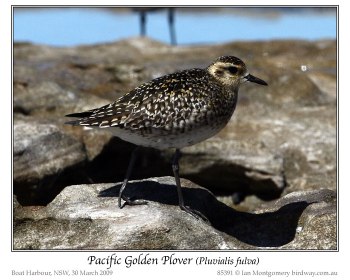

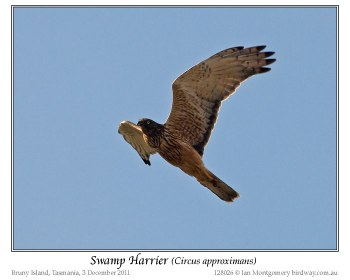

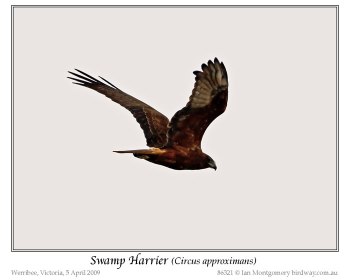

They are the vultures of the Southern Ocean, dealing with the unsavoury task of cleaning up offal in bird and marine mammal colonies, a job they tackle with unsubtle enthusiasm. They’re also not above killing young and or weak chicks of penguins, so it’s not surprising that they are often regarded with some distaste. On land, they appear clumsy like other members of the family, but, as the first photo, can be surprisingly agile. this bird is a young adult with a restricted amount of off-white on the face and neck. Juveniles are brownish-black and the adults get progressively paler on the head and neck as they age. The one in the second photo is an older adult.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

The most important field-mark for distinguishing Southern and Northern Giant-Petrels is the colour of the bulbous tip to the bill: this is greenish in the Southern and pinkish-red in the Northern. This might seem an inconspicuous feature, but the contrast between the otherwise pinkish bill and greenish tip of the Southern species is fairly obvious, even at a distance and the field-mark holds true for juvenile birds as well. The other field-mark is the pale leading edge to the wing of adult Southern Giant-Petrels, visible in the third photo of a bird concentrating very hard on making a gentle landing on the beach at Macquarie Island. This particular bird looked very pleased with itself after landing as you can see by following this link.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

Both species nest on islands all around the Southern Ocean, and their distributions overlap, though only the Southern breeds on the coast of Antarctica and only the Northern breeds on the Sub-Antartic Islands of New Zealand. Both nest on Macquarie Island, so there seems to be no doubt that they are different species despite their similarities, even though there is a population on Gough Island that is intermediate and may be hybrid (Northern plumage with greenish bill-tip). About 10% of the adult Southern population on Macquarie Island belong to a white morph and have almost complete white plumage with a few dark spots, fourth and fifth photos. With a little imagination, this looks like ermine and makes these birds look almost regal compared with their decidedly grungy relatives. Interestingly, about 1% of the juveniles fledged on Macquarie are albino with completely white plumage and pink bill, legs and feet, but they don’t appear to survive to adulthood. The Northern Giant-Petrel doesn’t have a white morph.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

Both species occur in mainland Australian waters but usually offshore and usually as juveniles. The juveniles have silky dark plumage and look quite dapper. The sixth photo shows one of each species off the coast of Victoria, and you can see the difference in bill colour.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) and Northern Giant Petrel (Macronectes halli) juv by Ian

The seventh photo shows a juvenile in flight south of New Zealand. The pale leading edge to the wing of the Southern species is absent in juveniles, but this photo illustrates the point I made earlier that the bill colour is visible even in birds at a distance.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) by Ian

If you’re observant, you may have noticed that I’ve tried changing the font of the species English and scientific names – the seventh photo shows the old font. I chose this originally to copy the style of 19th Century bird artists such as the French-America John James Audubon (below). Recently a member of the list made the point that the scientific name in particular was hard to read in the old font (Edwardian Script). The new one (Apple Chancery) is italic-looking and doesn’t have a separate italic style, so I’ve need to underline the scientific name instead to conform to scientific naming conventions. If you feel strongly about either the old or new fonts, let me know ian@birdway.com.au so I can make a decision whether to make the change permanent.

Audubon’s Shearwater (Puffinus lherminieri) Drawing Ian

The Dusky Shearwater, incidentally, is now known as Audubon’s Shearwater (Puffinus lherminieri) and is part of the Little Shearwater species complex. He encountered it off the coast of Florida: it breeds in the Caribbean and on Cape Verde Is and has been recorded in Australia.

Best wishes

Ian

**************************************************

Ian Montgomery, Birdway Pty Ltd,

454 Forestry Road, Bluewater, Qld 4818

Tel 0411 602 737 ian@birdway.com.au

Bird Photos http://www.birdway.com.au/

Recorder Society http://www.nqrs.org.au

Lee’s Addition:

The birds of the air, and the fish of the sea, and whatever passes along the paths of the seas. (Psalms 8:8 AMP)

Here is a hint for the photo that has the two juveniles in it; the bulbous tip of the front one is green and the back one is pink. Thanks, Ian, for introducing us to more interesting birds. Their beaks are quite interesting. See Formed By Him – Sea Birds That Drink Seawater, for an article for an explanation of that beak.

Wikipedia, with editing, also has this to say about this bird: The Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus), also known as the Antarctic Giant Petrel, Giant Fulmar, Stinker, and Stinkpot, is a large seabird of the southern oceans. Its distribution overlaps broadly with the similar Northern Giant Petrel, though it overall is centered slightly further south.

It, like all members of the Procellariiformes have certain features that set them apart from other birds. First, they have nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called naricorns. Although the nostrils on the Petrels are on the top of the bill. The bills of all Procellariiformes are also unique in that they are split into between 7 and 9 horny plates. Finally, they produce a stomach oil made up of wax esters and triglycerides that is stored in the proventriculus. This is used against predators as well as an energy rich food source for chicks and for the adults during their long flights. They also have a salt gland that is situated above the nasal passage and helps desalinate their bodies, due to the high amount of ocean water that they imbibe; it excretes a concentrated saline solution from the nostrils.

Southern Giant Petrel (Macronectes giganteus) egg ©WikiC

The Southern Giant Petrel achieves maturity at six or seven years of age; however the average age of first breeding is ten years. Its breeding season begins in October. Its nest is a mound of moss, grass, and stones with a depression in the center and located on bare or grassy ground. They form loose colonies except in the Falkland Islands where the colonies are much larger. One egg is laid and is incubated for 55–66 days. When the white chick is born it is brooded for two to three weeks and it fledges at 104–132 days.

See:

*