SEABIRDS AND CETACEANS BOTH LOVE OCEAN-CATCH FISH!

(With Extra Information about How Norwegians and Americans Scrutinize Saltwater Serenades)

Dr. James J. S. Johnson

HUMPBACK WHALE (The Bermudian Magazine)

And God created great whales [tannînim], and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly, after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind; and God saw that it was good. (Genesis 1:21)

SEABIRDS AND CETACEANS BOTH LOVE OCEAN-CATCH FISH!

Ocean-catch fish is enjoyed, daily at sea, by both whales and seabirds. Accordingly, it is not surprising to find seabirds hovering over places where whales are feeding on oceanic fish.

Seabirds and whales share a special bond; they both love fish. Seabirds are often found at the top of the food web and can also function as indicators of ecosystem health. Seeing seabirds on the surface is a possible sign that whales are also feeding underneath. This is especially the case for humpback and North Atlantic Right whales, which are the baleen whales at the most risk in the Northern Atlantic.

Researchers wanted to know how often seeing a specific kind of seabird known as great shearwaters coincided with the presence of whales. To do this, they spent five years surveying both the Gulf of Maine and the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary near Boston.

[Quoting Ashley Mickens, “Where There Are Birds … There Are Whales?”, OCEANBITES (September 30, 2022), posted at https://oceanbites.org/where-there-are-birds-there-are-whales/#:~:text=Seabirds%20are%20often%20found%20at%20the%20top%20of,at%20the%20most%20risk%20in%20the%20Northern%20Atlantic — citing Tammy L. Silva, et al., “Exploring the Use of Seabirds as a Dynamic Ocean Management Tool to Mitigate Anthropogenic Risk to Large Whales”, FRONTIERS IN MARINE SCIENCE, 9:861 (2022).

SOOTY SHEARWATERS feeding on fish near shore (LifeinaSkillet.com photo credit)

In short, shearwaters tagged with GPS tags can be used to locate large whales feeding on fish, with such location information being useful for reducing the risks of collisions at sea between those whales and human-driven watercraft.

Based on their unique life-history characteristics, seabirds equipped with satellite tags could serve as valuable tools for implementing dynamic management. Procellariid seabirds are highly mobile, enabling them to respond quickly to changing environmental conditions over large spatial scales and their top position in food webs means their location may indicate areas of high forage fish abundance. Their role as ecological indicators (Velarde et al., 2019) position seabirds as attractive sentinels for monitoring changes in marine ecosystems, fluctuations in abundance and distribution of forage fishes, and for identifying areas of high productivity where top predators, including whales and ocean users may congregate. Further, tags applied to seabirds are less expensive, less invasive, and can last longer than tags on large whales.

Great shearwaters (Ardenna gravis; hereafter shearwaters) are one of the most common pelagic seabirds in the Gulf of Maine (GOM) (Powers, 1983), including in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (SBNMS), a 2180 km2 federal marine protected area (MPA) (SBNMS unpublished data). In the sanctuary, shearwaters overlap with humpback whales. Both species consistently overlap with sand lance (Ammodytes dubius), their preferred prey in this region (Payne et al., 1986; Powers et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020) and shearwaters are often seen foraging with surface-feeding humpback whales. Sand lance are also found in specific, sandy substrates and previous work also shows that humpbacks and shearwaters use many of the same habitats throughout the GOM (Robbins, 2007; Powers et al., 2017; Powers et al., 2020). This suggests that satellite-tagged great shearwaters could indicate humpback whale locations at wider scales, and that some of these static locations may lend themselves to dynamic management. While the idea of investigating the use of tagged shearwaters to locate humpback whale aggregations is supported by previous work, considering tagged shearwaters as indicators of right whales is also of interest for two reasons: (1) they are critically endangered and management tools to drastically reduce vessel strikes and entanglements is desperately needed; and ( 2) right whales and sand lance in the GOM feed primarily on copepods, including Calanus finmarchicus (Wishner et al., 1995; Murison and Gaskin, 1989; Mayo and Marx, 1990; Suca et al., 2021), making it plausible that shearwaters feeding on sand lance may overlap with right whales.

[Quoting Tammy L. Silva, et al., “Exploring the Use of Seabirds as a Dynamic Ocean Management Tool to Mitigate Anthropogenic Risk to Large Whales”, FRONTIERS IN MARINE SCIENCE, 9:861 (2022).]

This research buttresses earlier reports from the National Marine Sanctuaries, as noted during A.D.2020 by Anne Smrcina.

NEW INSIGHTS ON SHEARWATERS’ WINTER RANGE

Humpback whales, great shearwaters (foreground), and gulls feasting on school of sand lance in Stellwagen Bank Nat’l Marine Sanctuary.

Photo: SBNMS/WCNE under NOAA Fisheries Permit #981-1707

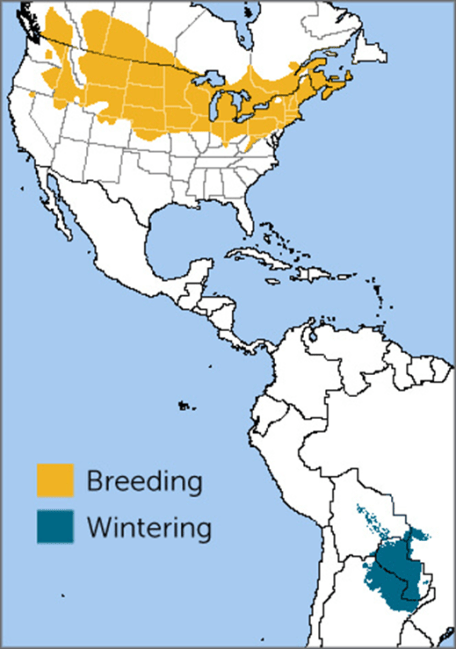

In spring months, humpback whale mothers bring their calves to Stellwagen Bank to wean them as they teach them to hunt schools of fish. Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary serves as their summer nursery. Researchers now believe that the bank, as well as the greater Gulf of Maine, serves as a nursery for another important but very different species – the great shearwater, an abundant seabird locally, and a global traveler.

A sanctuary-led research team found that this seabird species, which “summers” on islands in the southern South Atlantic and along the Patagonian shelf off Argentina December-February, uses the Gulf of Maine as a “winter” nursery during the months of approximately July-November. More mature birds extend their range to the Scotian Shelf off Nova Scotia and the Grand Banks off Newfoundland.

[Quoting Anne Smrcina, “New Research Provides Insight into Shearwaters, Humpbacks, their Prey, and Future Management Implications”, NATIONAL MARINES SANCTUARIES NEWS (NOAA, November 2020), posted at https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/nov20/shearwaters-winter-range.html .] Anne Smrcina’s research report, for NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), cited the findings published in the MARINE ORNITHOLOGY journal, specifically K. D. Powers, et al., “Spatiotemporal Characterization of Non-breeding Great Shearwaters (Ardenna gravis) within their Wintering Range”, MARINE ORNITHOLOGY, 48:215-229 (2020).

SHEARWATER tagged with GPS tracker (photo by Peter Flood / NOAA)

================================================================

Now that’s something to sing about!

(Extra Information about How Norwegians and Americans Scrutinize Saltwater Serenades)

What is “whale-song”? Music-like whale talk! Whales are cetaceans, a category of whales and whale-like marine mammals, e.g., porpoises and dolphins. Our English word “cetacean” derives from the Greek noun kêtos (κητος) which appears in Matthew 12:40 (as “whale”), so “whales” are mentioned in Scripture.

Consider Genesis 1:21, quoted above. Consider also Job 7:12, Ezekiel 32:2, and Matthew 12:40, as well as the reference in Lamentations 4:3a (“Even the sea monsters draw out the breast, they give suck to their young ones:”).

For a short YouTube on humpback “songs” (by Oceania iWhales), check out https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=whale+song&view=detail&mid=080AA0FA37A93E87AB44080AA0FA37A93E87AB44&FORM=VIRE (about 3 minutes long).

For a video (by NatGeoOceans) on researching Blue Whales, review this YouTube: https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=Blue+Whale+Sounds&&view=detail&mid=FA613CEC5B6570EB96A8FA613CEC5B6570EB96A8&&FORM=VRDGAR (video is about 6 minutes, with information on how Blue Whales are observed and recorded).

How can you describe the variety of whale-song sounds? Screeching, shrieking, grunting, wailing, moaning, groaning, rumbling, buzzing, rattling, sqeaking, squealing, clicking, whistling, whining, rumbling, sputtering, and some low-noted sounds that might be embarrassing if emitted by humans.

BOWHEAD WHALE (NOAA Fisheries photo)

BOWHEAD WHALES

Three Norwegian biologists (Dr. Øystein Wiig, Dr. Kit M. Kovacs, and Dr. Christian Lydersen), with an American oceanographer (Dr. Kate M. Stafford), have been studying whale-song—specifically, the songs sung by Bowhead whales from the polar waters of Svalbard, an island territory of Norway.

Almost all mammals communicate using sound, but few species produce complex songs. Two baleen whales sing complex songs that change annually, though only the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) has received much research attention. This study focuses on the other baleen whale singer, the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus). Members of the Spitsbergen bowhead whale population produced 184 different song types over a 3-year period, based on duty-cycled recordings from a site in Fram Strait in the northeast Atlantic. Distinct song types were recorded over short periods, lasting at most some months. …

Complex ‘song’ in mammals is rare. While many mammalian taxa produce repetitive ‘calls’, sometimes called advertisement songs, few mammals produce vocal displays akin to bird song, which is defined by multiple frequencies and amplitude-modulated elements combined into phrases and organized in long bouts. Such songs have been documented in only a few mammalian species, including some bats (Chiroptera), gibbons (Hylobatidae), mice (Scotinomys spp.), rock hyraxes (Procavia capensis), and two great whales, humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) and bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) whales [BLUE WHALES sing simplistic loud-and-rhythmic “rap music”, so they are excluded from this listing of “complex song” vocalists!]. With the exception of gibbons, in which males and females duet, complex songs in mammals are thought to be produced only by males. Male mammals are thought to sing to defend territories, advertise their quality, attract mates or some combination of these functions.

The song in baleen whales has been studied extensively only in humpback whales, which sing similar songs within a season across a whole population. The structure of that song gradually evolves [sic – erroneous terminology in original] over the season in unison and transfer of song types has been documented to occur directionally from one population to another over a period of years. Humpback whale songs are composed of a hierarchy from units to sub-phrases to phrases to themes.

Less is known about the songs of bowhead whales compared with humpback whales, but bowhead whale songs generally consist of a single phrase that includes amplitude- and frequency-modulated elements repeated in bouts, with two different sounds often produced simultaneously.

A pilot study from the Fram Strait in 2008 – 2009 provided the first indication that tens of song types were produced by bowhead whales in this region within a single overwinter period. No year-round studies of song diversity exist for other bowhead whale populations although multiple song types in a single year have been documented for two other populations. …

The diversity and interannual variability in songs of bowhead whales in this 3-year study are rivalled only by a few species of songbirds.

Among other mammalian singers, mice and gibbons tend to produce highly stereotyped and repetitive songs with few elements. Variation in rock hyrax and bat songs is primarily through changes in the arrangement of units.

Humpback whales produce complex songs that are similar within a year. Although the repertoire of any one individual bowhead whale in this study cannot be determined, the catalogue of song types (184) is remarkably varied.

It is not known whether individual bowhead whales sing multiple song types in a season, but some are known to share the same song type in the same period in the Bering– Chukchi–Beaufort (BCB) population. Nor is it known if individual bowhead whales maintain the same song throughout their lifetime or if they switch within and/or between years.

One explanation for the very high song diversity in the Spitsbergen bowhead whale population could be that the animals occupying this area in modern times include immigrants from both the BCB and the eastern Canada–western Greenland bowhead populations.

Until recently, these populations have been assumed to be isolated from each other due to extensive, impenetrable sea ice cover in the High Arctic.

However, in the past few decades, extreme declines in sea ice extent and thickness may have facilitated contact between these populations. However, even if this region contains bowhead whales from multiple populations, this does not fully explain the high numbers of different song types recorded in this study or the lack of recurrence of song types from year to year.

It is plausible that the bowhead whales in the Fram Strait are simply a remnant of the original Spitsbergen [Svalbard] population that survived the extreme historical levels of exploitation. The influence of small population size on song diversity is conflicted; some studies suggest song diversity increases in smaller populations, although others have found that reduced or isolated populations exhibit a reduction in song diversity and produce simpler songs.

In some species, females appear to prefer a diverse song repertoire, suggesting that increased complexity of singing might confer reproductive advantages. A recent study of howler monkeys (Alouatta spp.) documented tradeoffs in male reproductive characteristics based on (temporary) social structure: in groups with fewer males, or smaller social groups, males invested more in vocal displays as a reproductive tactic. …

Bowhead whales are the only High Arctic resident baleen whale. Thus, interspecific identification via song may not confer the same selective [sic – should say “reproductive success”] advantage for bowheads that it might for other cetacean species. This could reduce selection pressure [sic – mystical-magic jargon in original] on song stereotypy, allowing for greater variation in song types as a result of a long-term cultural mutation in songs, or song novelty itself might confer an advantage.

Because bowhead whales sing underwater, in heavy ice during the polar night, a nuanced understanding of the variable syntax of this species will be difficult to obtain.

Nevertheless, the singing behaviour of Spitsbergen bowhead whales, in which tens of distinct song types are produced annually, makes them remarkable among mammals.

[Quoting from Kate M. Stafford, Christian Lydersen, Øystein Wiig, & Kit M. Kovacs, “Extreme Diversity in the Songs of Spitsbergen’s Bowhead Whales”, BIOLOGY LETTERS, 14:20180056 (April 2018).]

But, before Bowhead Whale songs were scrutinized, it was the singing of Humpback Whales that was reported — surprisingly revealing a submarine world of sound communications that most folks would never have imagined.

HUMPBACK WHALE (Nat’l Wildlife Federation photo)

HUMPBACK WHALES

One of the most unusual music recordings to sell into the “multi-platinum” sales level was an LP album produced in AD1970, called “Songs of the Humpback Whale”, recorded by bio-acoustician Dr. Roger Payne, who had (with Scott McVay) discovered humpback “whale-song” (i.e., complex sonic arrangements of sound, sent for communicative purposes) during the AD1967 breeding season.

Prior to AD1970 Dr. Payne had studied echolocation (i.e., “sonar”) in bats, as well as auditory localization in owls, so (biologically speaking) he had “ears to hear” how animals use vocalized sounds to send and receive information to others of their own kind. Some of Dr. Payne’s work was shared with his wife (married AD1960; divorced AD1985), Katharine Boynton Payne, who noticed the predictable patterns of humpback whale-song, such as “rhymes”. Acoustical research included spectrograms of whale vocalizations, portraying sound peaks, valleys, and gaps—somewhat (according to her) like musical “melodies” and “rhythms”.

To this day, apparently, “Songs of the Humpback Whale” is the best-selling nature sound recording, commercially speaking. The sensation-causing album (“Songs of the Humpback Whale”) presented diverse whale vocalizations (i.e., “whale songs”) that surprised many, promptly selling more than 100,000 copies.

Some of Dr. Payne’s research on whale-song appeared early, published in SCIENCE magazine, as follows:

(1) Humpback whales ( Megaptera novaeangliae ) produce a series of beautiful and varied sounds for a period of 7 to 30 minutes and then repeat the same series with considerable precision. We call such a performance “singing” and each repeated series of sounds a “song.”

(2) All prolonged sound patterns (recorded so far) of this species are in song form, and each individual adheres to its own song type.

(3) There seem to be several song types around which whales construct their songs, but individual variations are pronounced (there is only a very rough species-specific song pattern).

(4) Songs are repeated without any obvious pause between them; thus song sessions may continue for several hours.

(5) The sequence of themes in successive songs by the same individual is the same. Although the number of phrases per theme varies, no theme is ever completely omitted in our sample.

(6) Loud sounds in the ocean, for example dynamite blasts, do not seem to affect the whale’s songs.

(7) The sex of the performer of any of the songs we have studied is unknown.

(8) The function of the songs is unknown.

[Quoting from Roger S. Payne & Scott McVay, “Songs of Humpback Whales”, SCIENCE, 173(3997):585-597 (August 13th 1971).]

HUMPBACK WHALES (ScienceAlert photo)

Dr. Payne eventually suggested that both Blue Whales and “fin whales” (a category of baleen whales also called “finback whales” or “rorqual whales”, which include the Common Rorqual, a/k/a “herring whale” and “razorback whale”) could send communicative sounds, underwater, across an entire ocean, and this phenomenon has been since confirmed by research.

Payne later collaborated with IMAX to produce a unique movie, “Whales: An Unforgettable Journey”.

Others, of course, have joined in the research, studying humpback whale-song in the Atlantic Ocean.

For example, Howard E. Winn and Lois King K. Winn, both at the University of Rhode Island, summarized some of their research as follows:

Songs of the humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae were recorded and analyzed from Grand Turks in the Bahamas to Venezuela. … The [humpback whale] song is produced only in the winter tropical calving grounds, just before the whales arrive on the banks. Redundancy is high in that syllables, motifs, phrases and the entire song are repeated. Low, intermediate, and high-frequency sounds are scattered throughout the song. One sound is associated with blowing. The song appears to be partially different each year and there are some differences within a year between banks which may indicate that dialects are present. It is suggested that songs from other populations are quite different. The apparent yearly changes do not occur at one point in time. Only single individuals produce the song and they are hypothesized to be young, sexually mature males. …

It has been known for 25 years that the humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae produces a variety of sounds. However, it was not until 1971 that Payne and McVay (1971), using recordings of humpbacks from Bermuda, demonstrated that the sounds are produced in an ordered sequence. In 1970, Winnet al. verified their findings by showing that humpbacks in Mona Passage, Puerto Rico, also produce a highly patterned song which lasts from 6 to 35 min and is repeated after surfacing.

Variation in the song’s organization has been explained by a number of hypotheses. Winn (1974, 1975) hypothesized that various song types might rep resent geographic herd dialects. Recently, Payne and Payne (in press) studied additional songs from Bermuda and concluded that the song changes each year. The song’s social and behavioral context has also been studied.

Apparently the song is produced only by single, isolated individuals, primarily while they are in the tropics during the winter (Winn et al., 1970; and this paper). They calve and mate during this period, but generally do not feed (Tomilin, 1967).

The song of [humpback patterns include] … “moans and cries”; to “yups or ups and snores”; to “whos or wos and yups”; to “ees and oos”; to “cries and groans”; and finally to varied “snores and cries”. Snores, cries and other sounds can be found in different themes from year to year; yet, invariably one finds a set pattern of changing themes, in a fixed order. Several times humpbacks have breached in the middle of their song and then restarted the song from the beginning or at some different part of the song.

[Quoting from H. E. Winn & L. K. Winn, “The song of the humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae in the West Indies”, MARINE BIOLOGY, 47(2):97-114 (January 1st 1978).]

Many years after their earliest research together, Dr. Roger Payne joined with his ex-wife (Katharine Payne) to describe their 19 years of studies of humpback whale-song, especially as observed in the Atlantic Ocean near Bermuda:

163 songs of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) recorded near Bermuda during April and May of 13 years between 1957 and 1975 have been analysed as continuous sound spectrograms and compared. In each year’s sample, all whales were singing basically the same song. However, the song was changing conspicuously and progressively with time so that songs separated by a number of years were very different in content. All the songs showed basic structural similarities so that it is possible to define a song form which characterizes songs from many years. …

An analysis, of the songs sung by groups of whales, shows that normal singing continues even when whales are close enough, presumably, to hear each other. Such analysis demonstrates inter– and intra– individual variability, none of which is as great as the variation between songs of consecutive years. We do not understand the significance of changing songs.

We know of no other non-human animal for which such dramatic non-reversing changes appear in the display pattern of an entire population as part of their normal behavior.

[Quoting from Katharine Payne & Roger Payne, “Large Scale Changes over 19 Years in Songs of Humpback Whales in Bermuda”, ETHOLOGY, 68(2):89-114 (April 26th 2010).]

BLUE WHALES

Recently Dr. Ana Širović, a Croatian-born oceanographer at University of California—San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography (based in La Jolla), reported observations of the Blue Whale—and its habit of underwater singing. Some of these observations were published by Craig Welch, in NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, as follows:

By analyzing thousands of calls from more than 100 whales over 14 years, scientists are learning how these secretive beasts spend their time.

BLUE WHALE (Natural World Safaris photo)

The biggest animal to ever live is also the loudest, and it likes to sing at sunset, babble into the night, talk quietly with those nearby, and shout to colleagues 60 miles away.

The blue whale, which can grow to 100 feet long and weigh more than a house, is a veritable chatterbox, especially males, vocalizing several different low-frequency sounds. And for years scientists had only the vaguest notion of when and why these giants of the sea make all those sounds. … In the first effort of its kind, Ana Širović, an oceanographer at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, and her team scoured a collection of more than 4,500 recordings of blue whale sounds taken from underwater microphones at over a dozen locations over 14 years, from 2002 to 2016, in southern California. The researchers then sync[h]ed the recordings with the movements of 121 whales that had been tagged with suction-cup trackers. What they learned challenged many assumptions about these noisy beasts.

Singing Males

Blue whales of both sexes produce several types of single-note calls, but only males sing. Males are also far noisier, and make different sounds for different reasons, but scientists aren’t always sure what those reasons are. For example, scientists had long assumed that one type of short call was used at meal time. But, instead, males and females frequently produced these vocalizations during dives that didn’t involve foraging at all. “It’s like the two behaviors are entirely separate,” says Širović.

The calls also change with the seasons and with time of day. Some single-note calls seem to occur more often when whales are returning from deep dives. Those may help with pair-bonding, scientists say. Much like birds, which often break into sound as day fades, male blue whales also tend to sing at the end of the day. In some species, such as European robins and nightingales, singing is often adjusted as a means of conserving energy, and energy may be a factor with blue whales as well. But unlike birds, Širović says, “blue whale songs propagate over tens of kilometers or even 100 kilometers.” And when they’re singing, male blues dive deeper. “I think what they are doing by regulating depth is changing the distance over which they’re calling, Širović says. “Individual calls are probably to animals nearby. They may be trying to reach much farther with singing. That’s kind of cool.” She assumes the singing—especially since it’s limited to just males—may somehow be linked to searching for mates. But no one has ever witnessed blue whale reproduction, so she can’t say for certain.

Songs of the Species

Širović has found there are similarities across many species, especially whales in the same family, such as blues, brydes, and sei whales. Males are the predominant singers and there seem to be peak calling seasons. But there are differences, too. Unlike blues, with their deep melodic songs, fin whales don’t really change notes. Their songs, instead, are produced using a single note, but with a rhythmic beat.

And unlike some dolphin species, such as killer whale, it’s not clear whether blues have distinctive voices. So far it appears they do not. “We can’t always tell whether there are 10 calls from 10 whales or one whale calling 10 times,” Širović says. “So far, we can’t really tell Joe Blue Whale from Betty Blue Whale.”

BLUE WHALE breaching surface (oumarinespecies.com photo)

This Blue Whale vocalization research, by Dr. Širović, was summarized recently by creation scientist David Coppedge, as follows:

Blue whales—the largest animals in the ocean—are talented singers, too, but little has been known about the music of these secretive beasts.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC reported on a 14-year effort by Scripps Institute in California to decode the vocalizations of 100 blue whales.

Since the sound travels for miles, they could pick up the sounds remotely with underwater microphones, but they also sync[h]ed the sounds with individual whales by outfitting them with suction-cup trackers.

The results were surprising, changing assumptions about blue whale behavior . . . Both sexes vocalize, but only the males ‘sing’, the researchers found. They’re also the loudest. The reasons for all the noise are not well known, but the males seem to begin their ‘deep melodic songs’ around sunset, serenading into the night, probably to attract mates. … The more details you learn about living things, the less excuse you have to chalk it up to evolution.

[Quoting from David Coppedge, “Underwater Troubadours”, CREATION MATTERS, 23(2):8-11 (March-April 2018).]

===================================================================

Dr. James J. S. Johnson has taught courses in biology, ecology, geography, limnology, and related topics (since the mid-AD1990s) for Dallas Christian College and other Texas colleges. A student (and traveler) of oceans and seashores, Jim has lectured as the onboard naturalist-historian (since the late AD1990s) aboard 9 different international cruise ships, including 4 visiting Alaska and the Inside Passage, with opportunities to see humpback whales, usually (but not always) from a safe distance. Jim is also a certified specialist in Nordic History & Geography (CNHG), and also in Nordic Wildlife Ecology (CNWE), who frequently gives presentations to the Norwegian Society of Texas (and similar groups). ><> JJSJ profjjsj@aol.com