Birds Illustrated by Color Photography – Revisited

Vol 1. May, 1897 No. 5

*

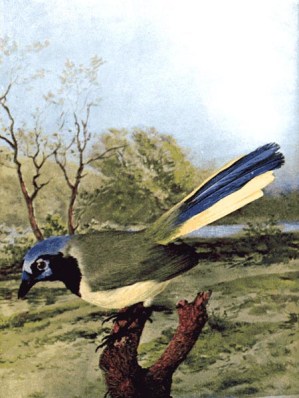

THE SCISSOR-TAILED FLYCATCHER.

LYCATCHERS are all interesting, and many of them are beautiful, but the Scissor-tailed species of Texas is especially attractive. They are also known as the Swallow-tailed Flycatcher, and more frequently as the “Texan Bird of Paradise.” It is a common summer resident throughout the greater portion of that state and the Indian Territory, and its breeding range extends northward into Southern Kansas. Occasionally it is found in southwestern Missouri, western Arkansas, and Illinois. It is accidental in the New England states, the Northwest Territory, and Canada. It arrives about the middle of March and returns to its winter home in Central America in October. Some of the birds remain in the vicinity of Galveston throughout the year, moving about in small flocks.

There is no denying that the gracefulness of the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher should well entitle him to the admiration of bird-lovers, and he is certain to be noticed wherever he goes. The long outer tail feathers he can open and close at will. His appearance is most pleasing to the eye when fluttering slowly from tree to tree on the rather open prairie, uttering his twittering notes, “Spee-spee.” When chasing each other in play or anger these birds have a harsh note like “Thish-thish,” not altogether agreeable. Extensive timber land is shunned by this Flycatcher, as it prefers more open country, though it is often seen in the edges of woods. It is not often seen on the ground, where its movements are rather awkward. Its amiability and social disposition are observed in the fact that several pairs will breed close to each other in perfect harmony. Birds smaller than itself are rarely molested by it, but it boldly attacks birds of prey. It is a restless bird, constantly on the lookout for passing insects, nearly all of which are caught on the wing and carried to a perch to be eaten. It eats moths, butterflies, beetles, grasshoppers, locusts, cotton worms, and, to some extent, berries. Its usefulness cannot be doubted. According to Major Bendire, these charming creatures seem to be steadily increasing in numbers, being far more common in many parts of Texas, where they are a matter of pride with the people, than they were twenty years ago.

The Scissor-tails begin housekeeping some time after their arrival from Central America, courting and love making occupying much time before the nest is built. They are not hard to please in the selection of a suitable nesting place, almost any tree standing alone being selected rather than a secluded situation. The nest is bulky, commonly resting on an exposed limb, and is made of any material that may be at hand. They nest in oaks, mesquite, honey locust, mulberry, pecan, and magnolia trees, as well as in small thorny shrubs, from five to forty feet from the ground. Rarely molested they become quite tame. Two broods are often raised. The eggs are usually five. They are hatched by the female in twelve days, while the male protects the nest from suspicious intruders. The young are fed entirely on insects and are able to leave the nest in two weeks. The eggs are clear white, with markings of brown, purple, and lavender spots and blotches.

Lee’s Addition:

I know all the birds of the mountains, And the wild beasts of the field are Mine. (Psalms 50:11 NKJV)

The Lord has given us another beautiful bird to enjoy. The Scissor-tailed Flycatchers are in the Tyrant Flycatchers – Tyrannidae Family. Adult birds have pale gray heads and upper parts, light underparts, salmon-pink flanks, and dark gray wings. Their extremely long, forked tails, which are black on top and white on the underside, are characteristic and unmistakable. At maturity, the bird may be up to 14.5 inches (37 cm) in length. Immature birds are duller in color and have shorter tails. A lot of these birds have been reported to be more than 40 cm.

They build a cup nest in isolated trees or shrubs, sometimes using artificial sites such as telephone poles near towns. The male performs a spectacular aerial display during courtship with his long tail forks streaming out behind him. Both parents feed the young. Like other kingbirds, they are very aggressive in defending their nest. Clutches contain three to six eggs.

In the summer, Scissor-tailed flycatchers feed mainly on insects (grasshoppers, robber-flies, and dragonflies), which they may catch by waiting on a perch and then flying out to catch them in flight (hawking). For additional food in the winter they will also eat some berries.

Since the article was written they are increased their range. Their breeding habitat is open shrubby country with scattered trees in the south-central states of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas; western portions of Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri; far eastern New Mexico; and northeastern Mexico. Reported sightings record occasional stray visitors as far north as southern Canada and as far east as Florida and Georgia. They migrate through the Gulf states of Mexico to their winter non-breeding range, from southern Mexico to Panama. Pre-migratory roosts and flocks flying south may contain as many as 1,000 birds.

The scissor-tailed flycatcher is the state bird of Oklahoma, and is displayed in flight with tail feathers spread on the reverse of the Oklahoma Commemorative Quarter.

There are actually four Scissor-tailed named birds in the world:

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher

Scissor-tailed Hummingbird

Scissor-tailed Kite

Scissor-tailed Nightjar

Birds Illustrated by Color Photography – Revisited – Introduction

The above article is the first article in the monthly serial that was started in January 1897 “designed to promote Knowledge of Bird-Live.” These include Color Photography, as they call them, today they are drawings. There are at least three Volumes that have been digitized by Project Gutenberg.

To see the whole series of – Birds Illustrated by Color Photography – Revisited

*

(Information from Wikipedia and other internet sources)

Next Article – The Prothonotary Yellow Warblers

Previous Article – The Black-Capped Chickadee

Links:

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher – All About Birds

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher – Wikipedia

Tyrant Flycatchers – Tyrannidae Family

*