While reading the Sunday paper, I noticed an article about the Cassin’s Auklet being in trouble. There is a big “die-off” happening on the West Coast that has scientist baffled. Wanted to find out about this bird, so here is some information about them.

Cassin’s Auklet (Ptychoramphus aleuticus) is a small, chunky seabird that ranges widely in the North Pacific. It nests in small burrows and because of its presence on well studied islands in British Columbia and off California it is one of the better known auks. It is named for John Cassin, a Pennsylvania businessman and naturalist.

They belong to the Alcidae – Auks Family which has 25 members. There are Auks, Murres, Guillemots, Murrelets, Auklets, and Puffins in family. Auks are superficially similar to penguins having black-and-white colours, upright posture and some of their habits. Nevertheless they are not closely related to penguins,

Auks live on the open sea and only go ashore for breeding, although some species, like the common guillemot, spend a great part of the year defending their nesting spot from others.

The Cassin’s Auklet are nondescript, usually dark above and pale below, with a small white mark above the eye. Its bill is overall dark with a pale spot, and its feet are blue. Unlike many other auks the Cassin’s auklet lacks dramatic breeding plumage, remaining the same over most of the year. “At sea it is usually identified by its flight, which is described as looking like a flying tennis ball”

“…Strong is thy dwellingplace, and thou puttest thy nest in a rock.” (Numbers 24:21b KJV)

The Cassin’s auklet nests in burrows on small islands, and in the southern area of its range may be found in the breeding colony year round. It either digs holes in the soil or uses natural cracks and crevices to nest in, also readily using man-made structures. Pairs will show a strong loyalty towards each other and to a nesting site for many years. Both the parents incubate the single white egg, returning to swap shifts at night to avoid being taken by predators such as the western gull or peregrine falcon. They also depart from the colony before dawn.

At sea Cassin’s Auklets feeds offshore, in clear often pelagic water, often associating with bathymetric landmarks such as underwater canyons and upwellings. Numbers at sea may be grossly underestimated because the bird moves away from ships at a distance of more than a kilometer. Recently their distribution around Triangle Island has been determined by telemetry. It feeds by diving underwater beating its wings for propulsion, hunting down large zooplankton, especially krill. It can dive to 30 m below the surface, and by some estimates 80 m

According to the article Pacific Coast Sea Bird Die-Off Puzzles Scientists: “Scientists are trying to figure out what’s behind the deaths of seabirds that have been found by the hundreds along the Pacific Coast since October. Mass die-offs …have been reported from British Columbia to San Luis Obispo, California.

“To be this lengthy and geographically widespread, I think is kind of unprecedented,” Phillip Johnson told the reporter.

“The birds appear to be starving to death, so experts don’t believe a toxin is the culprit…. But why the birds can’t find food is a mystery.”

“Researchers say it could be the result of a successful breeding season, leading to too many young birds competing for food. Unusually violent storms might be pushing the birds into areas they’re not used to or preventing them from foraging. Or a warmer, more acidic ocean could be affecting the supply of tiny zooplankton, such as krill, that the birds eat.”

On December 26th of 132 dead birds found on the beach at Tillamook, Oregon, 126 were Cassin’s Auklets.

One thing is for sure, this issue has not caught the Lord by surprise. We were given dominion over the birds and part of that is to help preserve our birds. I am glad the scientist are digging into this issue to hopefully find an answer.

“And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” (Genesis 1:26 KJV)

Cool Facts from About Birds

- The Cassin’s Auklet is the only alcid known to produce two broods in a single breeding season, at least in the southern part of the range where birds may be seen at nesting colonies every month of the year.

- Vulnerable to predators, especially large gulls, the Cassin’s Auklet tends to visit its nest at night.

- The Cassin’s Auklet is named for John Cassin, a Pennsylvania businessman and naturalist.

- A group of auks has many collective nouns, including a “colony”, “loomery”, and “raft” of auks.

(Information from Wikipedia and other internet sources)

*

- Pacific Coast Sea Bird Die-Off Puzzles Scientists

- Cassin’s Auklet – Channel Islands NPS

- Cassin’s Auklet – Wikipedia

- Cassin’s Auklet – All About Birds

- Cassin’s Auklet – WhatBird

- Alcidae – Auks Family.

- Wordless Birds

*

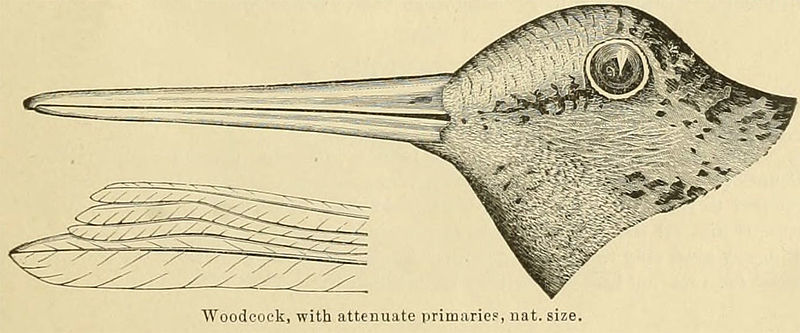

You can see by the photos that the “nape” can be narrow or very broad. Other birds have napes that are different colors, but do not have the word “nape” in their names. Some of the Woodpeckers that have napes were include above.

You can see by the photos that the “nape” can be narrow or very broad. Other birds have napes that are different colors, but do not have the word “nape” in their names. Some of the Woodpeckers that have napes were include above.