Balancing High Risks: Mountain Climbing and the First Amendment

By James J. S. Johnson

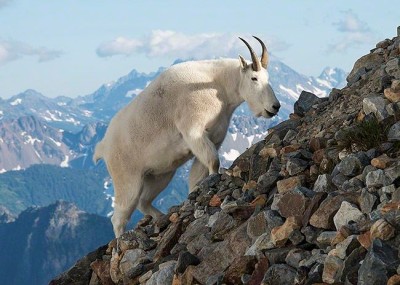

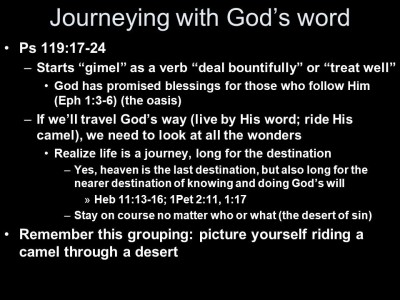

When an American astronaut reverently quotes from Psalm 24, and is promptly faulted by a critic—for “violating” the so-called “separation of church and state”(1)—it is time to learn a lesson about balance, from the agility of mountain goats, adroitly ambulating alpine ascents of the Rocky Mountains.

Indeed, mountain goats provide creation science “gems”, plus a picture of how we need balance in the political arena, where Christians are routinely shoved—and told to shut up, to avoid “offending” non-Christians. (Of course, it is offensive to Christians when they are told to “shut up”, but since when did unbelieving critics care about “offending” Christians?)

Why are mountain goats a picture of this problem? Because safely balancing a mountain goat’s body, on steep alpine slopes—and safely balancing individuals’ civil liberties (such as an astronaut’s religious freedom and free speech rights)—are both examples of high-stakes balancing acts. To appreciate this comparison (in this introductory review of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment), mountain goats must be matched to their intended natural habitat, just as the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment must be matched to its intended political context.

Consider, first, the agility of a mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), the sure-hoofed bovid that habituates the heights of North America’s Rocky Mountains and Cascade Range.(2)

“For those of us who admit to some fear of heights, the Mountain Goat is an animal to be admired … This shaggy animal, its back hunched in a manner somewhat suggestive of a Bison, is a master at negotiating the steepest of precipices. Mountain Goats are truly alpine creatures. They commonly rest on high-elevation snowfields and find most of their food among the plants of alpine meadows. Their hooves are structured to [optimize] balance and grip; the outer hoof is strongly reinforced and the bottom is lined with rubbery material, making the whole structure rather like a good hiking boot. These animals nonchalantly cross dizzying ledges, sometimes even at a trot.”(3)

In fact, the high-altitude dexterity of the mountain goat is so phenomenal that it routinely spends most of its time on precipitous terrain steeper than a 40o angle, and sometimes at pitches steeper than 60o!, especially during winter.(4)

Furthermore, the leg bones of the mountain goat are engineered to maximize a functional mix of precision balancing (such as perching all four hooves on a small spot), front-forward pulling power, propulsion leverage and maneuverability (for running and jumping), and stability (due to a low center of gravity) against tipping over.(4)

“A mountain goat climbs with three-point suspension. … Lifting one limb at a time [it] frequently pauses to assess the situation, tests the footing, and if needed turns back and selects a different route. Slow, sure consistency allows life on rock steeper than the angle of repose. Because they are most likely the ones to find themselves in a tight spot, kids do most of the go-for-broke climbing. Although a kid might take four or five missteps per year, it salvages the situation almost every time.”(4)

Thus, the mountain goats are aptly designed for moving on rocky slopes. Mountain goats are instinctively careful, and they apply their characteristic agility, as they test their environment. (Indeed, when predatory cougars try to attack them, the God-given instinct of mountain goats to flee, successfully, is often implemented by their agility and speed in and up these jagged rocky slopes and precipices!)

But without the right physical traits for maintaining balance on rugged rocks—traits which God installed on Day 6 of Creation Week—mountain goats could not thrive, as they do, upon the harsh talus slopes and felsenmeer of their high-elevation habitat.

“The [mountain goat hoofprint] track’s squarish imprint is created by the hoof’s spreading tips. The sides of the toes consist of hard keratin, like that of a horse hoof. Each foot’s two wraparound toenails are used to catch and hold on to cracks and tiny knobs. … The front edge of the hoof tapers to a point, which digs into dirt or packed snow when [it] is going uphill. In contrast to a horse’s concave hoof, which causes the animal to walk on the rim of its toenail, a [mountain] goat’s hoof has a flexible central pad that protrudes beyond the nail. The pad’s rough texture provides [skid-resistant] friction on smooth rock or ice yet is pliant enough to impress itself into irregularities on a stone. Four hooves X 2 toes per hoof = 8 gripping soles per animal. As [mountain] goats descend a slope the toes spread widely, adjusting tension to fine-tune the grip. … This feature makes them more likely to catch onto something. It also divides the downward force of the weight on the hoof so that some of the animal’s total weight is directed sideways. Because there is less net force on each downward [pressure] line, the foot is less likely to slide. Think of it as the fanning out of downward forces over numerous points of friction.”(4)

In a word, BALANCE. God purposefully designed high-elevation mountain goats for balance, because living life among high alpine rocks is a high-risk lifestyle.

Yet the same is equally true to balancing religious liberty rights (and responsibilities) in American society. Legitimate needs of both “church” and “state” are deliberately balanced with the God-given personal liberty rights of individuals. Like a mountain goat perched atop a precarious precipice, safeguarding those God-given religious freedoms is no lackadaisical endeavor. The securing of those fundamental freedoms was not (and is not) easily obtained, nor is it easy to maintain those freedoms amidst the ubiquitously power-greedy politics of both “church” and “state”.(5)

In a word, the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment is purposefully designed for BALANCE.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”. (5)

It is to this legal text that the “separation of church and state” concept is frequently attached. However, not all opinions are equal, regarding what that phrase of 16 words (in the First Amendment) mean. Why? Because, as a matter of honesty and valid interpretation, the real meaning of any message must be matched to the message-composer’s intent.(6)

Thus, the only legitimate understanding of the First Amendment’s meaning is the understanding that matches the meaning assigned to it by the (human) source of its words.(5),(6),(7)

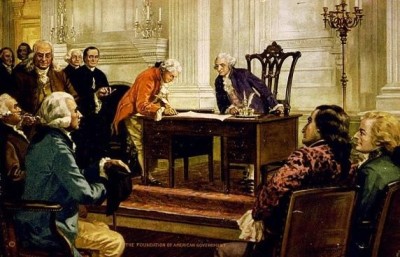

Yet, as a text drafted by statesmen of the late 1700s (principally by James Madison, who condensed an earlier version by George Mason), the authorial intent balanced a rejection of government-“established” church organizations, with affirmation of peaceful expression of individual religious beliefs and moral values.(6)

In other words, the First Amendment anticipated that Christians may freely express their religious viewpoints, at the personal level—yet Congress shall not officially endorse (“establish”) any specific ecclesiastical organizations, such as Baptists or Presbyterians or Anglicans or Methodists. This balancing of freedom and order—free exercise of religion, without any federal sponsorship of a particular religious denomination or hierarchy—fits the overall checks-and-balances equilibrium designed in 1791.(6)

“The real object of the First Amendment was not to countenance, much less to advance, Mohammedanism, or Judaism, or infidelity, by prostrating Christianity; but to exclude all rivalry among Christian sects, and to prevent any national establishment which should give to a [religious] hierarchy the exclusive patronage of the national government.”(8)

To put it mildly, this political balancing act is neither easily obtained nor easily maintained. But this balance was carefully planned for–intended—by America’s founding fathers. Yet now the phrase “separation of church and state” is used to force-fit an off-balanced understanding of the First Amendment. How did that happen?

In short, the constitutional jurisprudence of America became “evolutionized”, during the late 1800s, upsetting the proper balance between religious liberty and governmental interference.(5),(6),(7),(8),(9)

“Twentieth-century jurisprudence is based on a Darwinian world view. Life [supposedly] evolves, men [supposedly] evolve, society [supposedly] evolves, and therefore laws and constitutions [supposedly] evolve. According to the Darwinian principle, the Constitution’s meaning evolves and changes with time. … [Thus modern judges, implementing evolutionary humanism as jurists, my disagree about what a law “now means”] — But neither the majority nor the minority [of such evolutionary law judges] deny the basic evolutionary interpretation. They merely question at which stage of the evolutionary scale we are! This is not the way the founding fathers viewed constitutional interpretation. They saw the Constitution as the supreme law, and also as a covenant or contract. The Constitution like all legal documents was viewed as a fixed document, to be interpreted according to its plain meaning. And if its meaning was ambiguous as applied to a specific situation, it was to be interpreted according to the intent of those who wrote it, signed it, and ratified it. James Madison expressed this view when he wrote, ‘(If) the sense in which the Constitution was accepted and ratified by the Nation … be not the guide in expounding it, there can be no security for a faithful exercise of its powers’.”(9)

How evolutionary thinking infected American law will be reviewed, God willing, in a sequel to this introductory article.(10) Meanwhile, don’t believe it when someone tells you that the First Amendment “prohibits” an individual astronaut from reverently reading his Bible in space—or from sharing that personal fact via Facebook.(1)

And, as you appreciate the originally intended balance, designed in the First Amendment, don’t forget to thank God—for how He equipped agile mountain goats, to inhabit some of the most precarious places in the Rocky Mountains, as He exhibits (and we enjoy learning about) His creative glory and bioengineering genius.(2)

References

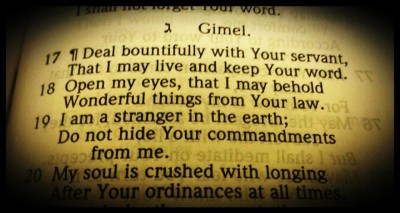

(1) On April 3rd of AD2016, via Facebook, U.S. astronaut Jeff Williams said: “We finally have a quiet Sunday and I’m reading, ‘The Earth is the LORD’s and all that fills it’ in Psalm 24 and viewing this sight [referring to photographs of Earth, seen from the International Space Station]. No matter how long you’re here [in space], the grandeur strikes and the wonder never fades.” To this posting a God-hating protest retorted, on Col. Jeff Williams’ Facebook page: “Jeff Williams could you please leave your personal religious views out of your public posts. You are a government employee. In America we have a separation of church and state. Don’t use your publicly funded position to promote personal views. Teachers shouldn’t and neither should astronauts. I enjoy the photos from space. I have followed astronauts photos for over two years without religious bias in the captions. Your post elevates (no pun intended) man’s divisiveness on Earth to Space. Please keep it private and keep posting these wonderful scientific pictures without the religious OPINIONS.”

(2) The rope-like “backbone” ridge chain of North America’s West is called the Western Cordillera. Included in its geographic system are the Rocky Mountains and the Cascade Range, the primary high-elevation range of most North American mountain goats. George Constanz, Ice, Fire, and Nutcrackers: A Rocky Mountain Ecology (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014), page 215.

(3) John Kricher, A Field Guide to Rocky Mountain and Southwest Forests (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), pages 235-236. As illustrated in Job 39:1, Israel’s mountain goat is named for how this bearded climber masters its rocky alpine habitat: ya‘alê-sâla‘ literally means “ascender of cliff-rock”. See also Psalm 104:18a.

(4) Constanz, Rocky Mountain Ecology, pages 224-226, with quotes frompages 225-226.

(5) U.S. Constitution, First Amendment (Free Exercise and Establishment clauses), ratified 1791. The vast majority of the world’s nations prohibit the “free exercise” for religious liberty, either by establishing a specific religion to the prejudice of others, or by persecuting theistic religions in general. The most thorough historical analysis of the First Amendment is provided in Rector, etc., of Holy Trinity Church v. United States, 143 U.S. 457, 12 S.Ct. 511 (1892), by Justice David Josiah Brewer. To bypass the jurisprudential relevance, of the Holy Trinity Church ruling, is to demonstrate careless misunderstanding of what the First Amendment was originally designed (and originally used) to accomplish. The balancing of civil government powers, ordained by God’s delegation, with jurisdictional limits to facilitate religious freedom, accords with relevant Scriptures, e.g., Matthew 22:21; Romans 13:1-4; Daniel 2:21 & 4:25—and with Israel’s separation of religious offices (tribe of Levi) from the monarchy (tribe of Judah).

(6) George Mason’s religious liberty tenet, which he had drafted (12 years earlier) for the Virginia Declaration of Rights, became the precursor for Virginia’s proposal (to Congress) to approve a religious freedom amendment for the “new” Constitution: “That Religion or the Duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by Reason and Conviction, not by Force or violence, and therefore all men have an equal, natural, and unalienable Right to the free Exercise of Religion according to the Dictates of Conscience, and that no particular religious Sect or Society of Christians ought to be favored or established by Law in preference to others.” Notably, the entire Bill of Rights (i.e., Amendments 1 through 10) limited federal government powers. Ironically, most of the Constitution’s later amendments have expanded those powers. John Eidsmoe, Institute on the Constitution: A Study on Christianity and the Law of the Land (Marlborough, NH: Plymouth Rock Foundation, 1995), pages 71-73. See also John Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of our Founding Fathers (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1987), pages 77-178, especially pages 93-112. Ironically, Thomas Jefferson (author of the phrase “separation of church and state”) was undeniably absent—in France!—during the Constitution’s drafting and early ratification (which processes prompted the Bill of Rights amendments), so his opinion of the First Amendment’s “intent” is interpretatively irrelevant.

(7) Importantly, the First Amendment’s meaning is contextually blended to the axiological fabric of the Declaration of Independence (referring to our “Creator”, “Nature’s God”, “the Supreme Judge of the world”, and “Divine Providence”), and to the Christian worldview evidenced by the U.S. Constitution’s Article VII (which refers to Jesus Christ as “our Lord”).

(8) Eidsmoe, Institute on the Constitution, page 76, quoting Justice Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston: Hilliard, Gray & Co., 1833), vol. II, page 593.

(9) John Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of our Founding Fathers (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1987), pages 391-392, quoting James Madison.

(10) The evolutionary mantra-phrase, “natural selection”, promotes animistic powers to inanimate elements of “nature”, not dissimilar from the polytheistic nature-worship of the ancient pagans. See, e.g., James J. S. Johnson, “Norse and Germanic Mythology”, Chapter 14 in World Religions and Cults, Volume 2 (Green Leaf: Master Books, 2016, edited by Bodie Hodge & Roger Patterson), especially at pages 271-272 & 287-288. See also, accord, James J. S. Johnson, “How Can a Mechanical ‘Cardinal’ Make ‘Selections’?“. For a thorough analysis of this “bait-and-switch” tricky-terminology problem (of “science” falsely so-called), see generally Randy J. Guliuzza’s “Darwin’s Sacred Imposter: Natural Selection’s Idolatrous Trap“, Acts & Facts, 40(11):12-15 (November 2011).

![http://www.larkwire.com/static/content/images/ipad/LBNA1/Sharp-shinnedHawk.jpg ] Sharp-shinned Hawk (Accipiter striatus) ©Lakewire](https://leesbird.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/accipiters-and-alcids-hawk.jpg?w=400&h=316)