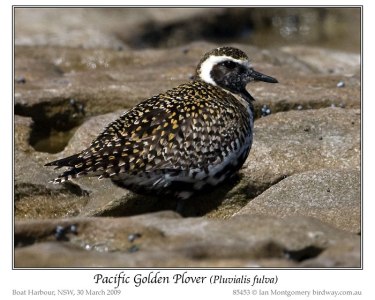

If a bird’s nest chance to be before you in the way, in any tree, or upon the ground, whether they be young ones [i.e., nestling infant birds], or eggs [i.e., not-yet-hatched baby birds], and the mother [’em is the usual Hebrew noun for “mother”] sitting upon the young, or upon the eggs, you shall not take the mother with the young. But you shall surely send forth the mother, and take the young [literally “children”] for yourself; that it may be well with you, and that you may prolong days. Deuteronomy 22:6-7

During mid-August (AD2015) my wife and I visited the Columbus Zoo (in Ohio), while vacationing, and I was surprised to see Trumpeter Swans (Cygnus buccinator) there — and I realized that the Trumpeter Swan illustrated the importance of Deuteronomy 22:6-7.

Seeing the snowy-white Trumpeter Swans, there, occurred during a telephone call, while we were viewing and identifying various animals, with our enthusiasm-exuding Ohio grandsons (who both call us Mimi and Farfar, the latter name being Norwegian for “father’s father”). The unexpected telephone call came from a caller in crisis, seeking legal advice, on how to interpret and apply a mix of federal statutes. It appeared that the call could not wait, till I returned to Texas – such is the lot and responsibility of a vacationing lawyer.

But a bird-watcher has his priorities! So, as we rounded a bend in the walking trail, and I saw a couple of Trumpeter Swans, I interrupted the phone call with “hold on just a minute”, then I half-screamed to the grandsons: “Look, boys – Trumpeter Swans! Look! Trumpeter Swans!”

Seeing these massive swans, up close, helps you to appreciate how huge they are. Trumpeter Swans are the heaviest of all birds that are “native” to North America – and one of the heaviest birds, alive today, that is capable of flight! Unlike other swans, the Trumpeter Swan has a distinctively black bill, a stark contrast to the all-white hue of its adult plumage.

The Trumpeter is a close cousin of Eurasia’s Whooper Swan [Cygnus cygnus], which I previously commented on, in an earlier blogpost about birdwatching in Iceland (please check out https://leesbird.com/2014/12/08/birdwatching-in-iceland-part-i/ .) The Trumpeter Swans did not “trumpet” while we observed them; however, their name is due to their habit of loudly vocalizing with a musical sound like a trumpet, similar to the vocal sounds of their Cygninae cousins, the Whooper Swans and Bewick Swans. Swans are shaped somewhat like geese, but swans grow larger and have longer (and proportionately thinner) necks. The poise and posture of swans, accented by their flexible and long necks, appear more elegant than that of geese, some say, although surely mama geese would disagree. Why are swan necks so lengthy and versatile? Imagine being nick-named “Edith Swan-neck” — that is the name by which historians remember the wife and widow of England’s last Saxon king, Harold Godwinson, who lost the Battle of Hastings to William the Conqueror, in AD1066. [ For more on that providentially historic battle, see http://www.norwegiansocietyoftexas.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/VikingHistory-GeoWash-ancestry-NST-AD2012.pdf . ] Geese have 17 to 23 neck vertebrae, yet swans have 24 or more! Trumpeters also bob their heads a lot, apparently as a form of visual communication with one another.

Back to the very busy (and very tiring) adventure at the Columbus Zoo in Ohio.

As we all excitedly discussed the Trumpeter Swans, so close to us then, my mind recalled how these quietly graceful and magnificently dignified swans were once very close to the extinction cliff. According to one study (by Banko, cited below), in AD1957, the United States then hosted only 488 Trumpeter Swans. It got even worse! In AD1932, fewer than 70 Trumpeter Swans were known to exist in all of America, with about half of them dwelling at or near Yellowstone National Park’s northwest section. Would the Trumpeter Swan go extinct like the Passenger Pigeon and the Dodo bird?

What a loss it would have been, if our earthly home had seen a permanent demise of such noble anatids, especially since they once teemed when America was founded!

Trumpeter Swans were once hunted in huge numbers – thousands were killed for their skins and/or feathers. Sir John Richardson (a Scottish scientist/surgeon who studied the Trumpeter extensively) once wrote that the Trumpeter Swan was “the most common Swan in the interior of the fur-counties. … It is to the trumpeter that the bulk of the Swan-skins imported by the Hudson’s Bay Company belong” [as quoted in Winston E. Banko, “The Trumpeter Swan: Its History, Habits, and Population in the United States”, North American Fauna, 63:1-214 (April 1960), a data-source used for much of this article]. The Trumpeter Swan was well-known of its migratory habits, ranging from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, according to ornithologist James Audubon:

“The Trumpeter Swans make their appearance on the lower portions of the waters of the Ohio about the end of October. They throw themselves at once into the larger ponds or lakes at no great distance from the river, giving a marked preference to those which are closely surrounded by dense and tall canebrakes, and there remain until the water is closed by ice, when they are forced to proceed southward. During mild winters I have seen Swans of this species in the ponds about Henderson [Kentucky] until the beginning of March, but only a few individuals, which may have stayed there to recover from their wounds. When the cold became intense, most of those which visited the Ohio would remove to the Mississippi, and proceed down that stream as the severity of the weather increased, or return if it diminished. . . . I have traced the winter migrations of this species as far southward as the Texas, where it is abundant at times, . . . At New Orleans . . . the Trumpeters are frequently exposed for sale in the markets, being procured on the ponds of the interior, and on the great lakes leading to the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. . . . The waters of the Arkansas and its tributaries are annually supplied with Trumpeter Swans, and the largest individual which I have examined was shot on a lake near the junction of that river with the Mississippi. It measured nearly ten feet in alar extent, and weighed above thirty-eight pounds.” [Quotation taken from Banko, on page 15.]

During AD1862 George Barnston, a Scottish-born Hudson’s Bay Company official in Canada, noticed the Trumpeter Swan’s remarkable migration habit, as it is seen in America’s Northwest:

“In the winter months all the northern regions are deserted by the swans, and from November to April large flocks are to be seen on the expanses of the large rivers of the Oregon territory and California, between the Cascade Range and the Pacific where the climate is particularly mild, and their favourite food abounds in the lakes and placid waters. Collected sometimes in great numbers, their silvery strings embellish the landscape, and form a part of the life and majesty of the scene.” [Quotation taken from Banko, on page 17.]

Records indicate that Trumpeter Swans were still present in “the states of Washington, Oregon, and California in the Pacific flyway ; Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, Nebraska, Icansas, and Texas in the Central flyway ; Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, and Louisiana in the Mississippi flyway ; and Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina in the Atlantic flyway to demonstrate that the trumpeter still appeared as a migrant or winter resident in those states during the last half of the 19th century”, according to Banko (at page 20). Banko further reported, in AD1960, that the marketable feathers of swans historically superceded the marketing of their skins (especially by the Hudson’s Bay Company), and soon the population numbers of North American swans were plummeting as swan feathers gained popularity as a glamorous ingredient in fancy hats for ladies, with less flamboyant quills being marketed as ink-pens. Even the famous Audubon, in AD1828, observed that American Indians engaged in swan hunts, in order to gain the prized plumage of these wondrous waterfowl, many of which feathers would ultimately be exported for resale to ladies of fashion in Europe! (Banko once served as Refuge Manager, Branch of Wildlife Refuges, for the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, part of the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Fish & Wildlife Service).

As transatlantic trade in fancy feathers burgeoned, the marketing of Trumpeter Swan plumage (as well as plumage of other large birds, such as flamingo, egret, heron, and many others), for fashionable female headgear, was driving the North American population of Trumpeter Swans toward regional extirpations and appeared aimed at a continental extinction, — unless regulatory brakes were somehow applied, with ameliorative conservation efforts to restore the population.

Many conservation efforts combined, to rescue the Trumpeter Swan’s perilous predicament, four of which were: (1) the Lacey Act of 1900, that banned trafficking in illegal wildlife; (2) the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, that implemented the migratory bird protection “convention” treaty, of AD1916, between America and Great Britain (f/b/o Canada); (3) President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 7023 (4-22-AD1935); and (4) the conservation-funding statute called the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration [Pittman-Robertson] Act of 1937. For more on this last federal wildlife conservation-funding law, please review “Crayfish, Caribou, and Scientific Evidence in the Wild”, posted at http://www.icr.org/article/8775 ).

Saving America’s Trumpeter Swan from near-extinction is largely due – humanly speaking – to the establishment of the Red Rock Lakes Migratory Waterfowl Refuge (n/k/a “Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge”), part of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem — located mostly within a 60-mile radius that includes portions of southwestern Montana, eastern Idaho, and northwestern Wyoming, including Yellowstone National Park, which itself includes a “Trumpeter Lake”. The Trumpeters have enjoyed dwelling in the Red Rock Lakes neighborhood for generations — for example, an aerial photograph during January AD1956 shows 80 of them on Culver Pond (east Culver Spring area, where warm spring waters, often found in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, keep the pond from freezing), on a day when the outside air was -20 degrees Fahrenheit! (See page 59 of Banko’s report, cited above.) This federal wildlife refuge was established by FDR’s presidential executive order (#7023), in AD1935, largely in reaction to the nadir-number of Trumpeter Swan count of less than 70 during AD1932.

According to the Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge’s official website (q.v., at http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Red_Rock_Lakes/about.html), this refuge now includes 51,386 acres, plus conservation easements totaling 23,806 acres, all of which blends into a marvelous mix of snowmelt-watered mountains, montane forests, flowing freshwater, and marshy meadows:

“Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge has often been called the most beautiful national wildlife refuge in the United States. The rugged Centennial Mountains, rising to more than 10,000 feet, provide a dramatic backdrop for this extremely remote Refuge in Southwest Montana’s Centennial Valley. Red Rock Lakes NWR encompasses primarily high mountain, wetland-riparian habitat–the largest in the Greater Yellowstone Area– and is located near the headwaters of the Missouri River. Several creeks flow into the refuge, creating the impressive Upper Red Rock Lake, River Marsh, and Lower Red Rock Lake. The snows of winter replenish the refuge’s lakes and wetlands that provide secluded habitat for many wetland birds, including the trumpeter swan, white-faced ibis, and black-crowned night herons. The Refuge also includes wet meadows, willow riparian, grasslands, and forest habitats. This [ecological] diversity provides habitat for other species such as sandhill cranes, long-billed curlews, peregrine falcons, eagles, hawks, moose, badgers, bears, wolves, pronghorns and native fish such as Arctic grayling and westslope cutthroat trout.” [Quoting from http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Red_Rock_Lakes/about.html ]

Trumpeter Swans are also seen afloat in lakes of Wyoming’s neighboring park, Grand Teton National Park, a scenic mountain-dominated park accented by the Snake River and Jackson Lake, and historically enjoyed, annually (in the summer), by many bankruptcy barristers (and their families), as they simultaneously attended the Norton Bankruptcy Law Institutes at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. The Trumpeter pairs are often seen as isolated pairs, each “owning” its own lake, yet these swans also congregate in gregarious flocks, especially in the Red Rock Lakes area.

[Canadians, especially in British Columbia and Alberta, have also been intensively involved in serious efforts to conserve Canada’s population of Trumpeter Swans, for more than 65 years – but this birding report mostly notices and focuses on the Trumpeter conservation efforts in the United States.]

Has FDR’s Executive Order 7023 been followed by conservation and restoration success, for the Trumpeter Swan? The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service website reports a happy “yes”:

“In 1932, fewer than 70 trumpeters were known to exist worldwide, at a location near Yellowstone National Park. This led to the establishment of Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in 1935. Red Rock Lakes is located in Montana’s Centennial Valley and is part of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Nearly half of the known trumpeter swans in 1932 were found in this area. Warm springs provide year-round open waters where swans find food and cover even in the coldest weather. Today, estimates show about 46,225 trumpeter swans reside in North America, including some 26,790 in the Pacific Coast population (Alaska, Yukon, and NW British Columbia) which winter on the Pacific Coast; 8,950 in Canada; about 9,809 in the Midwest; and about 487 in the tri-state area of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana (including the Red Rock Lakes refuge flock).” [Quoting from http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Red_Rock_Lakes/about.html ]

Sounds like a winner to me — from less than 70 to more than 46,000!

However, if only the wildlife conservation principle of Deuteronomy 22:6-7 (i.e., you can take the eggs and nestlings, but not the adult mother birds) had been practiced in North America, during the past 2 or 3 centuries, the continent’s Trumpeter Swan population would never have gotten so close to extinction. Moses not only mandated restrictions on excessively hunting avian wildlife (Deuteronomy 22:6-7), Moses also banned imprudent deforestation (Deuteronomy 20:19-20). Of course, creation conservation laws are always balanced to value human life over nonhuman life forms (Matthew 6:26-30; Psalm 8; Jonah 4:8-11). Yet the promulgated priority of stewardly usage of God’s creation – because all of creation is God’s property, ultimately, not ours! — traces all the way back to Creation Week, because even Adam was put into Eden “to dress it and to keep it” (Genesis 2:15), and Noah managed the greatest biodiversity protection project ever (Genesis chapters 6-9).

Humans have been eating domesticated birds, such as chicken and turkey, ever since Noah’s family disembarked the Ark (Genesis 9:3). People who raise domesticated fowl (such as chickens) are careful to preserve enough breeders so that they don’t eat up all of their fowl. [This illustrates the old adage about balancing give and take: if your input exceeds your output, your upkeep is your downfall!] Accordingly, chicken farmers avoid eating all of their chickens — it’s important to protect the reproductive success of your chickens if you want poultry eggs and/or chicken meat to eat, on a continuing basis! But what about wild birds? The private ownership principle that guides common sense, in raising chickens and other domesticated fowl, doesn’t work so well with wild birds (especially migratory birds), because they are not privately “owned” – so they are a “public” resource vulnerable to irresponsible “tragedy-of-the-commons” depletion.

And most swans are wild, so greedy over-hunting can endanger their population success.

Providentially, the eating of wild birds, such as wild swans, was restricted under Mosaic law, for good reason — wild bird populations can be extinguished if one generation of hunters gets too greedy.

If a bird’s nest chance to be before you in the way, in any tree, or upon the ground, whether they be young one [i.e., nestling infant birds], or eggs [i.e., not-yet-hatched baby birds], and the mother [’em is the usual Hebrew noun for “mother”] sitting upon the young, or upon the eggs, you shall not take the mother with the young. But you shall surely send forth the mother, and take the young [literally “children”] for yourself; that it may be well with you, and that you may prolong days. Deuteronomy 22:6-7

This is a simple law of predator-prey dynamics: if the predator population (i.e., the “eaters”) consume too many of the prey population (i.e., the “eatees”), the result is bad for both populations, because the prey population experiences negative population growth, a trend that can lead to its reproductive failure (and extirpation) if the excessive predation continues unabated.

Each generation of humans, therefore, needs to exercise wise stewardship of Earth’s food resources, so that adequate food resources will be available of posterity (i.e., later generations). When greed leads to over-hunting, the foreseeable consequence is bad for both the birds (whose population declines, generationally) and the humans (whose food resources decline, generationally).

Sad to say, mankind’s track record for respecting and heeding God’s Word, as it teaches us to be godly stewards of His creation (and to use it in ways that glorify Him, its rightful and only true Owner), all-too-often misses the mark (Romans 3:23).

What slow learners we all-too-often are! [For Genesis-based ecology perspectives, for this fallen “groaning” world, see http://www.icr.org/article/misreading-earths-groanings-why-evolutionists/ and http://www.icr.org/article/7486/ and http://www.icr.org/article/genesis-science-practical-not-just/ and http://www.icr.org/article/why-we-want-go-home/ .]

Meanwhile, may God have mercy on the people of America, by restoring to us a serious and reverent respect for the whole counsel of God (Acts 20:27), that He has given us in the Holy Bible, His holy Word. Only then, as we heartily heed His Word, will we properly appreciate and rightly treat His creation, including the Trumpeter Swan. And, only then, will we properly revere and appreciate Him as our Creator (and Redeemer). And living life responsibly on His earth, with that kind of reverence, would be far better than the fanciest feather in anyone’s cap!

by James J. S. Johnson

*

More articles by James J. S. Johnson

*