THE RED BREASTED MERGANSER.

HY this duck should be called red-breasted is not at first apparent, as at a distance the color can not be distinguished, but seen near, the reason is plain. It is a common bird in the United States in winter, where it is found in suitable localities in the months of May and June. It is also a resident of the far north, breeding abundantly in Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland. It is liberally supplied with names, as Red-Breasted Goosander or Sheldrake, Garbill, Sea Robin, etc.

There is a difference in opinion as to the nesting habits of the Red-Breast, some authorities claiming that, like the Wood Duck, the nest is placed in the cavity of a tree, others that it is usually found on the ground among brushwood, surrounded with tall grasses and at a short distance from water. Davie says that most generally it is concealed by a projecting rock or other object, the nest being made of leaves and mosses, lined with feathers and down, which are plucked from the breast of the bird. The observers are all probably correct, the bird adapting itself to the situation.

Fish is the chief diet of the Merganser, for which reason its flesh is rank and unpalatable. The Bird’s appetite is insatiable, devouring its food in such quantities that it has frequently to disgorge several times before it is able to rise from the water. This Duck can swallow fishes six or seven inches in length, and will attempt to swallow those of a larger size, choking in the effort.

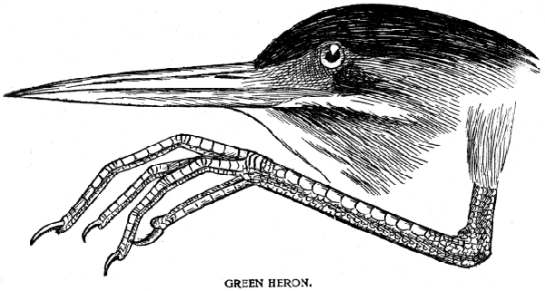

The term Merganser is derived from the plan of the bird’s bill, which is furnished with saw teeth fitting into each other.

The eggs of the Red-Breasted Merganser vary from six to twelve, are oval in shape, and are of a yellowish or reddish-drab, sometimes a dull buffy-green.

You may have seen pictures of this Duck, which frequently figures in dining rooms on the ornamental panels of stuffed game birds, but none which could cause you to remember its life-like appearance. You here see before you an actual Red-Breasted Merganser.

Birds Vol 2 #2 – The Red Breasted Merganser

Lee’s Addition:

Out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the air, and brought them to Adam to see what he would call them. And whatever Adam called each living creature, that was its name. (Genesis 2:19 NKJV)

Another of one of the Lord’s neat birds. Mergansers are found in the Anatidae – Ducks, Geese & Swans Family. There are six of them in two Genera. The Hooded Merganser in Lophodytes genus and the Auckland (extinct), Brazilian, Common, Red-breasted, and Scaly-sided in the Mergus genus.

The adult Red-breasted Merganser is 20–24 in (51–62 cm) long with a 28–34 in (70–86 cm) wingspan. It has a spiky crest and long thin red bill with serrated edges. The male has a dark head with a green sheen, a white neck with a rusty breast, a black back, and white underparts. Adult females have a rusty head and a greyish body. The juvenile is like the female, but lacks the white collar and has a smaller white wing patch.

The call of the female is a rasping prrak prrak, while the male gives a feeble hiccup-and-sneeze display call. (from xeno-canto)

Red-breasted Mergansers dive and swim underwater. They mainly eat small fish, but also aquatic insects, crustaceans, and frogs.

Its breeding habitat is freshwater lakes and rivers across northern North America, Greenland, Europe, and Asia. It nests in sheltered locations on the ground near water. It is migratory and many northern breeders winter in coastal waters further south.

It has been claimed to be the fastest bird in level flight, reaching speeds of 161 km/h (100 mph), but is disputed whether the White-throated Needletail is faster, reportedly flying at 170 km/h (105 mph).

Here is a video of a Common Merganser flipping his feet after diving for food that was given him at the Zoo Miami Wings of Asia Aviary – by me.

*

Birds Illustrated by Color Photography – Revisited – Introduction

The above article is the first article in the monthly serial that was started in January 1897 “designed to promote Knowledge of Bird-Live.” These include Color Photography, as they call them, today they are drawings. There are at least three Volumes that have been digitized by Project Gutenberg.

To see the whole series of – Birds Illustrated by Color Photography – Revisited

*

(Information from Wikipedia and other internet sources)

Next Article – The Yellow Legs

The Previous Article – The Kentucky Warbler

Links: